“The Japanese soldier is swaggering, self-confident, fanatically devoted to duty, and eager to achieve an honored place among Japan’s heroes. Being a prisoner is the worst possible disgrace that can befall him. When a Jap is captured, his commander orders a box of ashes be sent to his family. As far as they’re concerned, he’s dead.”

So declares a scene from the 1943 training film Interrogation of Enemy Airmen, showing a classroom of future Air Interrogation Officers (AIOs).

But please — never call a Japanese person a “Jap.” It is insulting, albeit commonly said in 1943.

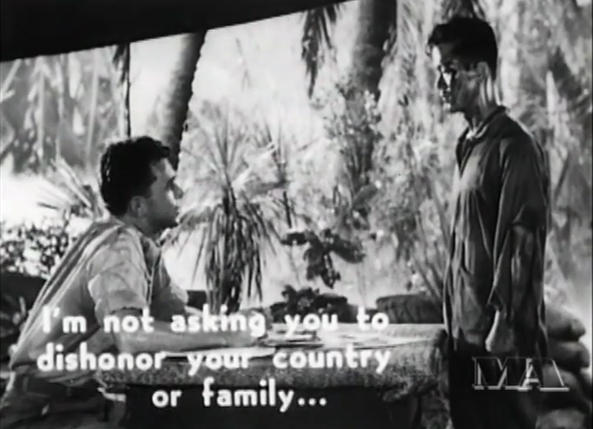

The film later portrays the interrogation of a Japanese pilot. The AIO, in a jungle camp on a Pacific island somewhere, sits behind a desk. The pilot is standing, looking ashamed. They speak in Japanese.

“I’m not asking you to dishonor your country or family,” explains the AIO. “I only want to clear up some minor points.”

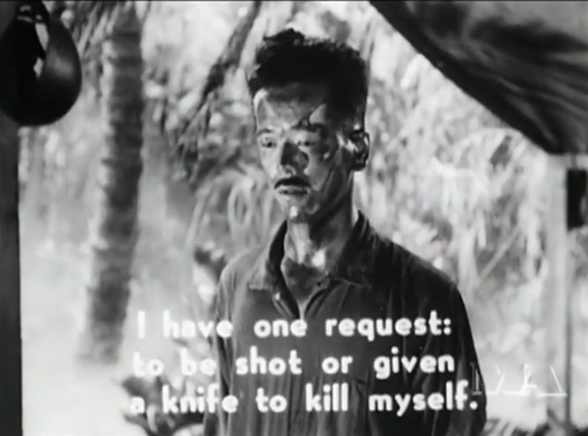

“I have one request,” the pilot responds. “To be shot, or given a knife to kill myself.”

.

.

“Don’t keep saying that,” the AIO replies. “Doubtless your officers told you to have this spirit — your officers who left the soldiers to die at Guadalcanal. They probably said you would be tortured by Americans. We will take good care of you. We will even send word through the Red Cross to your family that you are safe.”

“No! No! Please don’t do that!”

“Won’t your mother be glad to hear?”

“No, my family would be greatly shamed. It is better I die. They will be told I am dead.”

“You are too tired now to answer questions.” The AIO then summons a guard and orders him (in English), “Take this prisoner to the doctor, have him treated carefully and see that he gets a good meal and rest. And watch him every minute.”

Later, the AIO and the pilot meet again. After mutual greetings, both sit. “Feeling better?” the AIO asks.

“Much better.”

“See the doctor?”

“He was very kind.”

“You didn’t expect Americans to be like that? Now, about reporting you to the Red Cross…”

“No!”

“We should do that according to international law.”

“No! Please don’t do that! I am dead to my family and my country. But you have been kind and I appreciate that.”

“You see,” the AIO tells him, “you were our enemy, but despite that fact, we don’t hate you. Since you are dead as a Japanese, why not stay here, with us, and help? We won’t ask you to dishonor your country. You can help us and your countrymen who may be captured. With us, you can live a lot better than your people at home, better than at your base at Rabaul. That was your base?”

A slight pause.

“Yes. That was our base.”

“Now, there are just a few routine questions I would like to ask you.”

Film voiceover: “Looks easy, doesn’t it? Almost too easy. Well, it wouldn’t have been if the interrogator hadn’t known the psychology of the Japanese — that in war, capture is the ultimate disgrace and means the prisoner is dead. So our Jap has decided to be as comfortable dead as possible.”

It does look too easy.

Was it that easy in reality?

Actually, yes. Of all the nationalities in World War II, the Japanese were probably the easiest prisoners to interrogate. A major challenge was getting their American captors to realize this.

Since the Japanese Army and Navy didn’t expect any Japanese to surrender — and didn’t respect anyone who did — Japanese soldiers, sailors and airmen were not trained to know that, as prisoners, they had rights under international law. So when they were captured, many talked because they didn’t know any better. To their great surprise, they discovered that the Americans did not torture prisoners, were actually respectful, and in some ways even polite. That behavior prompted most Japanese to be polite in return, and being polite included talking. The most talkative Japanese tended to be those with wounds that their captors treated, because in the Japanese interpretation that medical treatment created a reciprocal obligation.

In Part 7, the indirect approach.

— John G. Heidenrich