The German Sergeant walks into the sparsely furnished interrogation room. Inside, Captain Schwartz is seated behind a desk. The Sergeant snaps to attention, renders a Nazi salute and shouts, “Heil Hitler!” That salute didn’t necessarily mean the Sergeant was a Nazi. In 1943, when Interrogation of Enemy Airmen was made, Nazi salutes were required throughout the German armed forces.

The German Sergeant walks into the sparsely furnished interrogation room. Inside, Captain Schwartz is seated behind a desk. The Sergeant snaps to attention, renders a Nazi salute and shouts, “Heil Hitler!” That salute didn’t necessarily mean the Sergeant was a Nazi. In 1943, when Interrogation of Enemy Airmen was made, Nazi salutes were required throughout the German armed forces.

Captain Schwartz, without bothering to stand, returns a more traditional salute. The two men then converse, in German.

“Sorry you’ve been smashed up,” Schwartz begins. “Lucky it wasn’t worse. Sit down.”

“I prefer to stand,” the Sergeant says tersely.

“Come,” replies Schwartz, smiling. “We respect your Luftwaffe training, especially KG 76. Your Commander Krug is one of the best. You’re entitled to relax.”

“Thank you, Sir.” He sits.

“Your family in Münich will be glad to hear you’re safe.”

“Will they hear?” asks the Sergeant, hope appearing on his face.

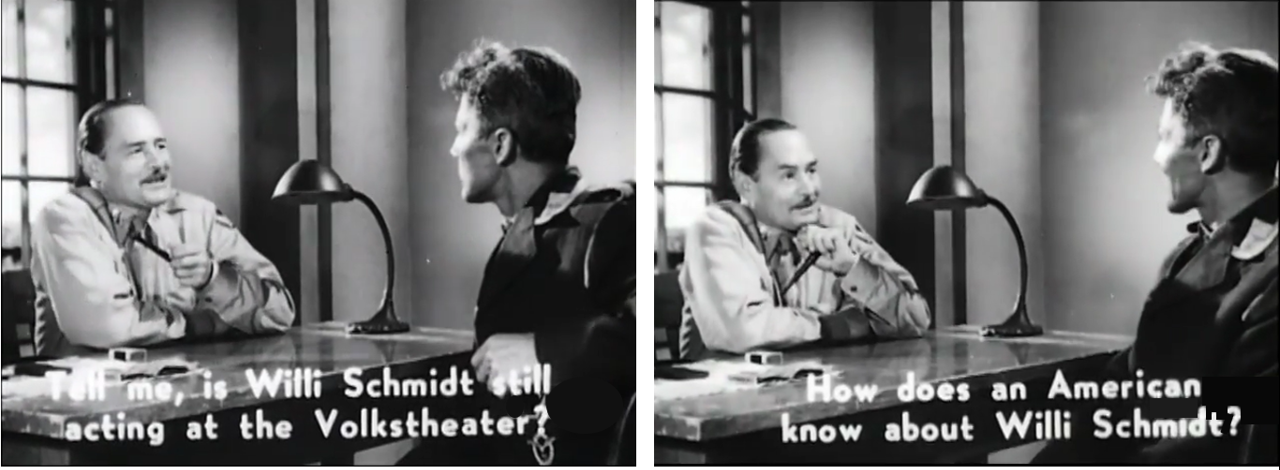

“I’ll see to it personally,” answers Schwartz, almost gleefully. “Tell me, is Willi Schmidt still acting at the Volkstheater?”

The question astounds the Sergeant. “How does an American know about Willi Schmidt?”

.

.

“I’ve seen him often,” Schwartz replies. (Notice that reply didn’t really answer the question.) “And Herr Ecker, at the Bayrischer Hof Bar, is he still making one part Vodka, one part Curacao?”

“Bayrischer Hof Special!” the Sergeant recalls, starting to laugh at the memory. “I had six when I was home in June.”

At this point, the scene focuses briefly on a hidden microphone inside a desk lamp, reminding the audience that Captain Schwartz’s assistants are secretly monitoring and recording the entire interrogation.

Schwartz laughs along with the Sergeant.

With the tone of a joke, Schwartz asks, “Did you have a long enough leave to recover?”

“I was on my way to a new unit.”

“From Russia?”

Suddenly the Sergeant remembers that he is being interrogated. “I didn’t say that!”

Schwartz responds in a calm voice, “I thought I noticed your ear was frozen.”

Surprised, and now unsure how to interpret the statement, the Sergeant touches his ear. Schwartz motions for him to relax. “Don’t be alarmed,” he says reassuringly. “There is no Gestapo here — and your Lieutenant well out of hearing.”

“I don’t worry about him.” The Sergeant’s tone is full of contempt. “He can’t harm me now, the Prussian blow-hard.”

“He gave me that impression too,” says Schwartz, “when he was blowing about his exploits at Stalingrad.”

Actually, the Lieutenant said nothing of the sort. Remember that Schwartz has not yet interrogated the Lieutenant, but is deceiving the Sergeant into believing otherwise. Now imagining that the Lieutenant has portrayed himself as a Stalingrad war hero, the Sergeant finds the whole idea too outrageous to not comment upon.

“Bah! He didn’t fight! He flew a Junkers-52 — a transport!”

Schwartz grins. “Not like flying that new Heinkel-117, eh?”

“No,” says the Sergeant, smiling at the thought — and then re-remembers the interrogation. “I mean, I don’t know anything about a new Heinkel-117!”

“I’m not asking you to betray military secrets,” says Schwartz. “We know all about your new Heinkels. Probably more than you.”

“That I doubt. You haven’t flown one.”

“Is it really so good?”

“Wonderful! Why, I flew one from Rouen to Paris in less than 30 minutes!”

Film voiceover: “And so the interrogation goes on and very successfully too, thanks Captain Schwartz’s training and common sense. You’ll notice he won the prisoner’s gratitude by promising to inform his family of his safety; how he established immediate contact through mutual interest in the Münich theater; how he played on the Bavarian’s prejudice against his Prussian lieutenant; and how he pretended he’d already seen Lieutenant Wedler and gotten information from him. How he pretended to know more about the new Heinkel-117 than the Sergeant, thereby piquing his vanity and getting him to talk. As a result, he is now in possession of valuable information. He knows the KG 76 has been moved from Russia; that the Sergeant has flown a new Heinkel-117; that they are probably based at Rouen.”

In Part 4, interrogating Lieutenant Wedler.

— John G. Heidenrich