We continue reviewing the World War II-era training film, Interrogation of Enemy Airmen.

The scene shifts to an office where an Air Interrogation Officer (AIO), Captain Schwartz, receives word that a German Junkers-88 aircraft has been shot down and its crew captured. Per standard procedure, the prisoners will be separated and kept silent, preventing them from concocting a shared, false story.

Typical personal belongings of a German bomber crew.

Soon the crew’s personal belongings, mostly stuff from their pockets, arrive for Schwartz’s examination. A minor document among the mix suggests that the aircraft was connected with Kampfgeschwader 76 (KG 76), a Luftwaffe bomber group. (The unit existed in reality too.) Through an effort which began months earlier, the intelligence personnel of the U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) have accumulated bits and pieces of information about almost every member of the German Luftwaffe they can learn anything about: from German newspaper clippings, intercepted radio messages, captured enemy documents, and the past interrogations of other German flyers taken prisoner. All of that information is sorted into files, from which Captain Schwartz learns that KG 76 is now headed by a Commander Krug. An assistant tells Schwartz that the downed airplane was piloted by a Lieutenant Wedler and co-piloted by a Sergeant. “Co-pilot!” Schwartz exclaims. “They must be running out of officers.” (Indeed, in 1943, they were.) The Sergeant’s personal belongings include a ticket stub from the Volkstheater in Münich, in Germany’s Bavaria region. Schwartz, having spent two years in Münich, knows the theater. (It existed in reality, too. It still does.)

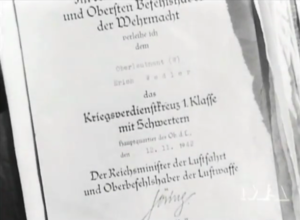

The Lieutenant’s belongings include a formal Citation for Bravery — signed by Field Marshal Herman Goering himself, head of the Luftwaffe. The film’s narrating voice says the Lieutenant must be mighty proud of this signed Citation to be carrying it into action.

The Lieutenant’s belongings include a formal Citation for Bravery — signed by Field Marshal Herman Goering himself, head of the Luftwaffe. The film’s narrating voice says the Lieutenant must be mighty proud of this signed Citation to be carrying it into action.

Proud, sure, but carried aboard an airplane? This is a training film, supposedly portraying the typical. Would that be typical? Yes, it would. In both Hitler’s Wehrmacht and Stalin’s Red Army, soldiers wore their medals even into combat, without camouflaging them. Displaying their medals inspired their fellow soldiers, especially subordinates.

An intelligence file on the Lieutenant already exists — something also typical in reality, especially if any enemy newspapers mentioned the officer’s name. Some intelligence analysts became mini-biographers. Even into the Cold War, both East and West endeavored to learn everything they could about the other side’s officers. “Our boy has quite a record,” Schwartz remarks, “…‘distinguished by his brutal treatment of the Poles’,” he quotes. Schwartz also learns that another German pilot named Wedler was recently shot down.

The Lieutenant is Prussian, a German ethnicity known for its aristocratic officers. The Sergeant is Bavarian. Schwartz decides to exploit their ethnic differences, if he can. He will interrogate the Sergeant first, but tell the Sergeant that the Lieutenant went first. Among Schwartz’s objectives: learn some things about a new German aircraft, the Heinkel-117.

Off to the interrogation room, which contains only a desk, a lamp, and two chairs. The interrogator will not take notes nor will he have to, for the room is bugged. Outside, his assistants are recording everything.

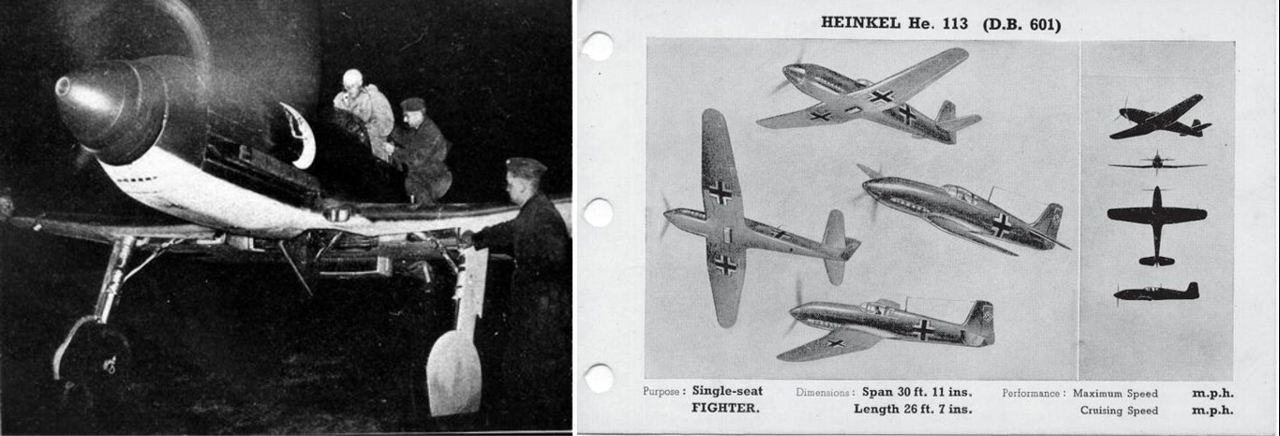

Now for some historical trivia: there was no such thing as a Heinkel-117 aircraft. The designation is fictional, to help the story along.

Nor did a Heinkel-113 aircraft exist, although in 1940 the Germans claimed that it did. Nazi magazines even printed photos of the supposed airplane, which was actually a cosmetically modified Heinkel 100 D-1 (shown at top and below, left). Why the Germans went to the trouble of perpetrating this deception is unclear. They had no obvious incentive. Nevertheless, the Allies completely fell for it. The illustration below, right, is from an Allied intelligence report in 1940. British Intelligence reported that the Heinkel-113 was “in production” and some Allied pilots even reported engaging it in air combat. No such luck.

.

.

In Part 3, interrogating the Sergeant.

— John G. Heidenrich