SIGINT is the acronym for Signals Intelligence.

Military units, before the invention of radio, used to communicate with each other by waving signal flags. One advantage of this method was exercise. One disadvantage was sheer exhaustion.

One unexpected benefit was eloquence.

One unexpected benefit was eloquence.

Sort of.

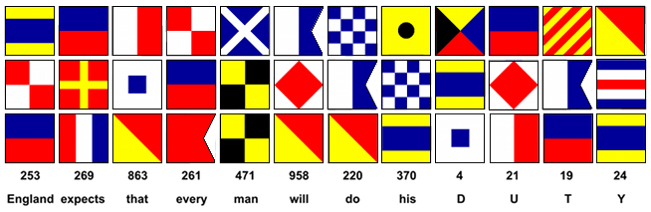

In 1805, in preparation for the naval Battle of Trafalgar, Admiral Lord Nelson of England’s Royal Navy wanted to boost the morale of his fleet by hoisting the following flag-coded message: “Nelson confides that every man will do his duty.”

When Nelson told his signal chief to fly this message, the chief was deeply moved. Moved to wonder why anybody would say confides.

What Nelson meant is that he had confidence in every man.

But the signal man didn’t have enough flags to spell out Nelson’s entire message, in part because encoding the average letter required three flags each. (Yes, three flags for each letter. How is that for bureaucratic efficiency?) Consequently, the signal chief was compelled to edit Nelson’s message, substituting words found in the naval codebook.

The result:

“England expects that every man will do this duty.”

To this day, British schoolboys are taught that the great Lord Nelson spoke those immortal words at his greatest victory, the Battle of Trafalgar. But he didn’t.

.

Accidental eloquence. And colorful!

Today signal flags are obsolete, and we have the more rational word communications, as in Communications Intelligence (COMINT). But the bureaucrats keep using the word signals. Talk about slow to change.

If the term Signals Intelligence still confuses you, just think radio signals, not flags.

During World War II, a few months after the Japanese attacked the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor and sunk several American battleships, the Japanese Navy wanted to finish off the American Navy by luring what was left into a massive trap set near the Pacific island of Midway. The Japanese had a brilliant plan. Even the Americans thought so — because the Americans had read it.

Alas for the Japanese, they discovered too late that a secret plan is only as good as the secret code used to send it.

The Americans entered the Battle of Midway with three aircraft carriers and left with two.

The Japanese entered with four carriers and left with none.

Somebody is having a really bad day.

While American code-breakers were busy reading Japanese coded messages, British code-breakers were busy reading German coded messages. It was an advantage so enormous and so secret that it became known as the Ultra secret. The few Brits privileged enough to read Ultra messages were given the password bigot. This allowed those lucky Brits with the special access to then ascertain the status of other Brits by asking such casual questions as “Are you a bigot?” Or “Are there any bigots in the room?”

To this day, the most secret, most sensitive programs in American and British Intelligence include an access roster of people privileged enough to be informed about it. And that access roster is called a bigot list.

You can’t make this stuff up.

Respectfully (because all my readers deserve respect),

Reginald Dipwipple

Secret Agent Extraordinaire