“Both [P. T.] Barnum and H. L. Mencken are said to have made the depressing observation that no one ever lost money by underestimating the intelligence of the American public. The remark has worldwide application. But the lack is not in intelligence, which is in plentiful supply; rather, the scarce commodity is systematic training in critical thinking.”

“Both [P. T.] Barnum and H. L. Mencken are said to have made the depressing observation that no one ever lost money by underestimating the intelligence of the American public. The remark has worldwide application. But the lack is not in intelligence, which is in plentiful supply; rather, the scarce commodity is systematic training in critical thinking.”

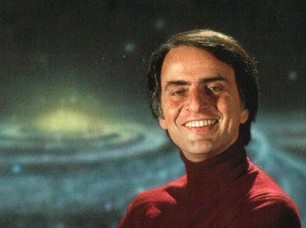

— Carl Sagan*, Astronomer and Scientist

* Although the quote is his own, the late Carl Sagan did not create nor endorse the REASON© method that is explained below, which was formulated after his death.

Critical thinking is an essential skill practiced by intelligence analysts and which every citizen can learn and use. For these reasons the Donovan Institute is committed to teaching critical thinking to the general public and has devised an easy method called REASON©. The following video script explains the method. Unfortunately, because the Donovan Institute is a small non-profit organization whose operating funds are extremely limited, we lack the funds to produce this video professionally and promote it on the Internet. Therefore, we are seeking to crowd-fund its production: our goal is a budget of $30,000 to transform this script into a professional video, including filming and some animation. If you care about critical thinking and want to encourage more critical thinking among your fellow citizens, please donate at least a small amount of money (U.S. currency only) to one or more of this project’s specific crowd-funding initiatives:

After our goal of $30,000 is reached, any additional donations to this project will be devoted to promoting the REASON© method.

Thank you for your donation!

Critical Thinking made easy — with advice from

the U.S. Founding Fathers

by John G. Heidenrich

At the William J. Donovan Institute for Global Strategic Intelligence, we offer the general public a broader understanding of the world, what you might call “big picture” thinking. We also explain how intelligence agencies like the CIA and FBI perform their missions. Part of this involves collecting and analyzing clues from multiple sources, including the Internet. Imagine the deductive logic of Sherlock Holmes and you get the idea. Analyzing information is a skill, and a big part is called critical thinking.

At the William J. Donovan Institute for Global Strategic Intelligence, we offer the general public a broader understanding of the world, what you might call “big picture” thinking. We also explain how intelligence agencies like the CIA and FBI perform their missions. Part of this involves collecting and analyzing clues from multiple sources, including the Internet. Imagine the deductive logic of Sherlock Holmes and you get the idea. Analyzing information is a skill, and a big part is called critical thinking.

Thomas Paine

Critical thinking does not mean to criticize merely to criticize. Critical thinking is a skilled way of thinking carefully to protect you from leaping to a false conclusion. We’re not born with this skill, just as we’re not born already speaking a language. But you can learn this skill fairly easily; and throughout history, it has proven essential to religious scholars, scientists, medical doctors — and the U.S. Founding Fathers. Although the label did not exist back then, the Founding Fathers learned critical thinking from their studies of history, science, religion and philosophy, and from their own experience.

Among the first of the Founding Fathers to advocate American independence was Thomas Paine, in a pamphlet he titled Common Sense. Paine warned that whereas “Reason obeys itself, ignorance submits to what is dictated to it.” Paine used the words reason and common sense because critical thinking is the common sense of using logical reasoning based on evidence and analysis.

Imagine someone claims that one plus one equals five. If the person isn’t making a joke, you can respond with logic and evidence to prove that one plus one equals two. That common sense behavior is a form of critical thinking. But if you or that person start to insult each other, that outburst is not critical thinking — because if you’re right about the facts, then you’re right. Period. You’ve won the argument, even if the other person doesn’t agree. He may claim that in his opinion, one plus one equals five. But his opinion cannot change the mathematical fact that one plus one equals two.

John Adams

John Adams put it this way: “Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passions, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.”

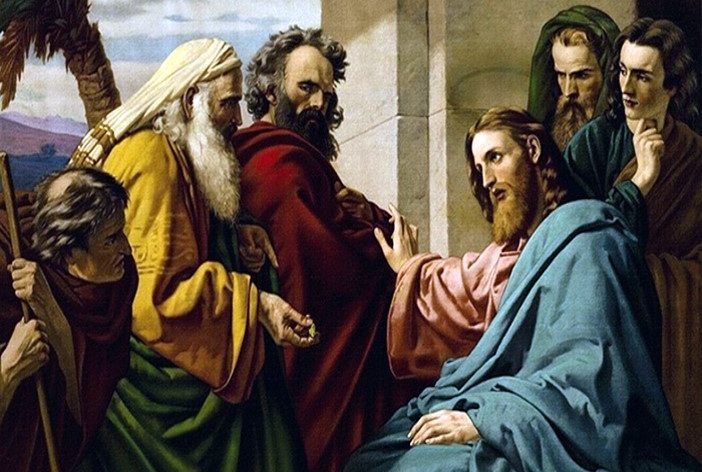

Unfortunately, there are some people who claim that critical thinking is somehow anti-religious. This is a strange claim, for no less than Jesus of Nazareth used critical thinking to debate some of the most educated men in ancient Judea. Jesus did not avoid the tough, probing questions that critical thinking raises. When Jesus said, “The Sabbath was made for Man, not Man for the Sabbath,” he did so in the context of asking and answering questions, showing how logic and evidence lead to this conclusion.

“The Sabbath was made for Man, not Man for the Sabbath.”

Whatever your faith and beliefs, critical thinking can help protect you against con artists and against being fooled by information that is either misleading, biased, or downright false. Too often people who use social media share information which is false without realizing it is false, because they assume that they’re just informing other people. But by not practicing critical thinking, they unwittingly spread errors and lies.

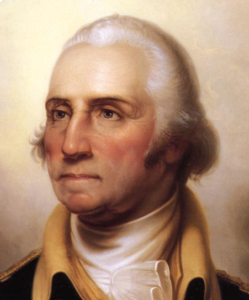

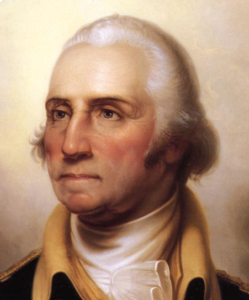

George Washington

George Washington warned of this, centuries before the Internet.

During the American Revolution, Washington was not only a General leading the Continental Army, he was a spy chief — running networks of secret agents. You might think that reading those spy reports would be fairly straightforward, but they often included rumors, exaggerations, and even lies planted by the enemy. His spies were brave but they weren’t always accurate. Fortunately, Washington knew the risks of accepting information at face value and, instead, used critical thinking. He warned, “When one side only of a story is heard and often repeated, the human mind becomes impressed with it — insensibly.”

By contrast, Adolf Hitler advocated the Big Lie: Tell a lie often enough and people start to believe it.

That is what happens when people fail to practice critical thinking.

There is no universal standard for what constitutes critical thinking. Therefore, the Donovan Institute has devised a few simple guidelines using the acronym R-E-A-S-O-N — REASON©. They are:

Review what you really know — versus what you assume.

Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.

Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

Skepticism includes a willingness to risk being wrong.

Opposite sources inform you of more than one side.

Nothing happens in isolation. Consider the context.

Don’t worry if this list seems a little overwhelming. These guidelines are actually easy to follow.

R… Review what you really know — versus what you assume.

The word critical comes from a Greek word meaning “to separate” — because an excellent way to investigate something is to study it in pieces. So, review the information you have while separating your assumptions from what you really know. An assumption is a belief but without enough evidence to prove it. You might be surprised by how many assumptions you make. Even experts are humbled when they think about it.

.

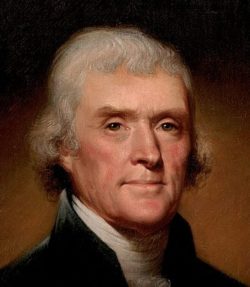

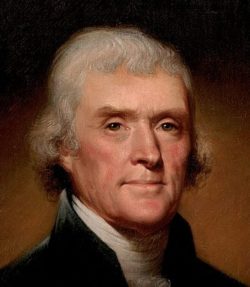

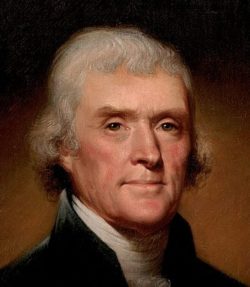

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson confessed: “He who knows most, knows best how little he knows.”

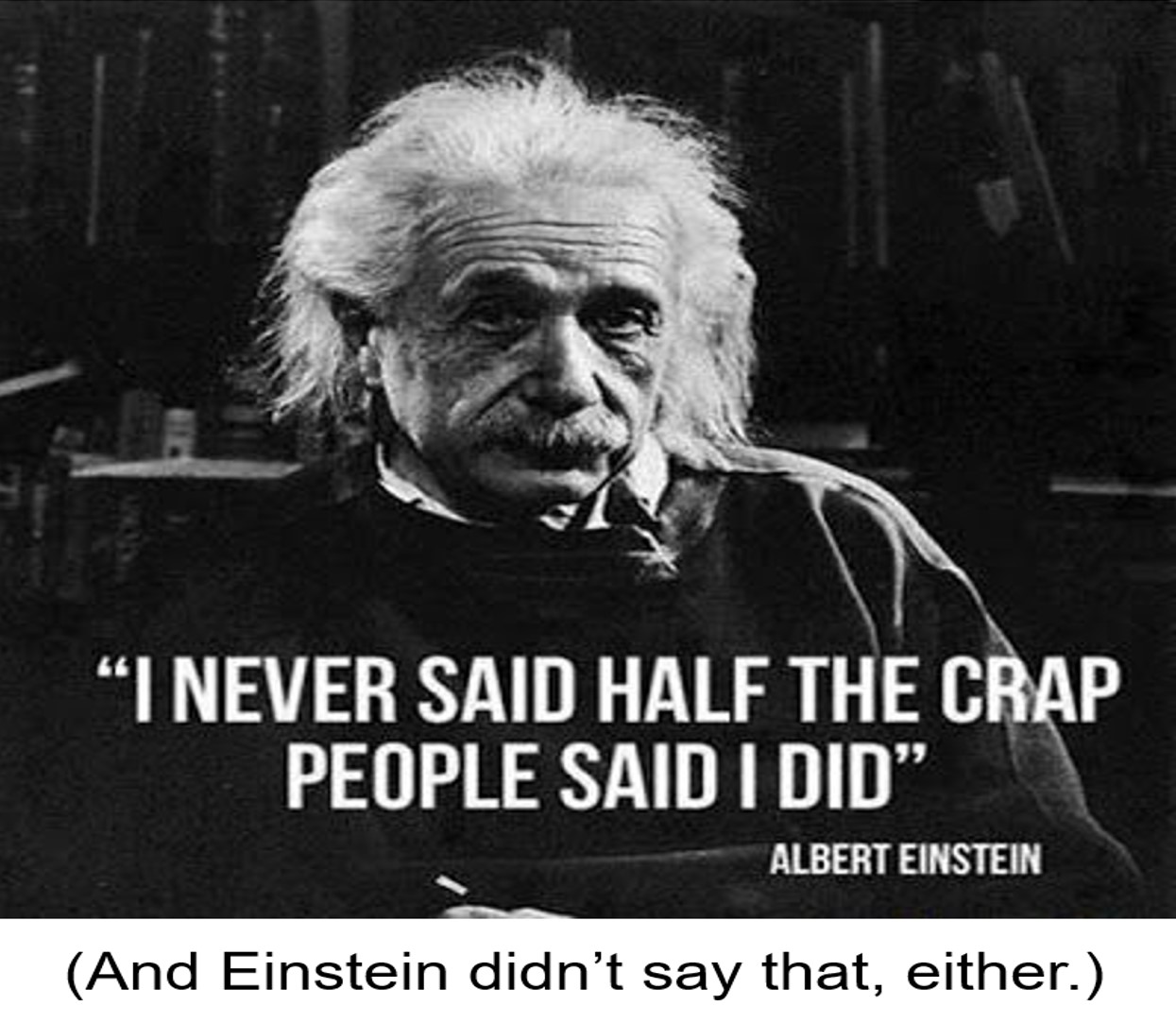

Jefferson’s quote alludes to an assumption that someone with an impressive background or title must always be right, about everything. Albert Einstein, for example, is quoted on a wide variety of subjects about which Einstein never claimed to be an expert. Even in physics, his only expertise, Einstein made mistakes even he admitted to. Expertise is no guarantee of being right; it merely improves the odds. Yet, too often, we’re not skeptical of those particular experts or personalities we like. We assume the best about them — but this clouds who they really are, what they actually say, and even why they’re saying it.

Imagine receiving an online article from a friend. Subconsciously, that article has already slipped past three of your mind’s skeptical filters. First, coming from a friend, you’re more likely to trust the article no matter what it says. Second, if you do like it, you’re even more likely to trust it because you want to. Third, since it looks like a news article, its very appearance implies credibility.

At this point critical thinking is urgent because you’re now extremely vulnerable to being deceived. So review the information again, this time very carefully. Maybe the article is totally accurate — or maybe the author got some facts wrong. Maybe the article is misleading, or reflects a political agenda. It could even be outright deceptive, what experts call disinformation. The original definition of fake news refers to information that is a deliberate lie — a lie so extreme, the perpetrator can be sued in court, because it is a crime. Unfortunately, disinformation and fake news on the Internet are all too common.

At this point critical thinking is urgent because you’re now extremely vulnerable to being deceived. So review the information again, this time very carefully. Maybe the article is totally accurate — or maybe the author got some facts wrong. Maybe the article is misleading, or reflects a political agenda. It could even be outright deceptive, what experts call disinformation. The original definition of fake news refers to information that is a deliberate lie — a lie so extreme, the perpetrator can be sued in court, because it is a crime. Unfortunately, disinformation and fake news on the Internet are all too common.

When you re-read the article, consider not only what it says but how it says it. What is the tone? Is it neutral, bland, matter-of-fact? Or is it more emotional, expressing anger, fear, or patriotic pride? Beware, because even scoundrels use patriotic language to manipulate people. In a genuine news report, the tone should never be emotional because the facts can speak for themselves. For example, an article reporting a natural disaster may provide numbers of the dead, injured and missing — and that tells you plenty. Emotional words are not required to get the message across. So when emotional words are used, beware, because the author may not be trying to inform you but to persuade you. The article could be a form of propaganda, with a few facts mixed-in to imply credibility.

.

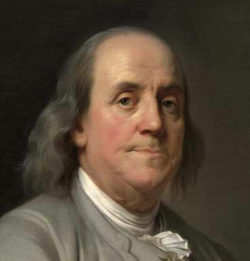

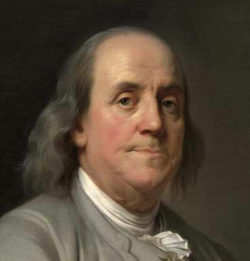

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin knew these tricks well, for he was a newspaper publisher, a political activist, and during the American Revolution, a propagandist. Ben Franklin joked: “Here comes the orator! — with his flood of words and his drop of reason.”

Propaganda tries to divide the world into supposedly good guys versus bad guys. Does the article say wonderful things about your favorite side, but nasty things about the other side? When these two extremes appear within the same article, be suspicious.

Does it quote statistics? A legitimate news article always provides the source of its statistics, often including a link so you can check for yourself.

Does it quote statistics? A legitimate news article always provides the source of its statistics, often including a link so you can check for yourself.

Is the website a blog? A blog is not an objective news source. It may share some news articles, but the blogger chose those particular articles, which means he’s trying to persuade you. Has he included any news articles that contradict what he believes?

Some blogs will portray themselves as news sites by including what appear to be news stories. Even if you like the site, however, remember to separate your assumptions from what you really know. Do you like the site because it stirs your emotions? That is not critical thinking. Does the site say it offers news from a particular political perspective? If so, it is admitting its own bias, which means it is not objective and doesn’t even claim to be. Who runs the site? Some supposed news sites are actually run by foreign governments, for propaganda purposes. Really — and those foreign ties may not even be hidden, because they’re mentioned somewhere on the site.

If the site has articles, read their headlines. Is the tone emotional? Maybe even cute? Is the aim to embarrass someone, a particular politician or party? Do most of the headlines favor one side? If the answer to any of these questions is yes, the site is probably at least biased. But if the tone of the headlines is neutral, unemotional, even boring, that implies more objective coverage because the headlines merely state the facts. And facts are often boring. But they’re still facts.

E… Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.

An extraordinary claim is an idea that is so radical that, if true, it would dramatically change our understanding of things. That’s a big change — too much change if it’s wrong. Therefore, extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence — proof which is so convincing, so absolute, that it persuades most experts if not most people. That doesn’t mean no dissenters whatsoever, but relatively few, for even dissenters can be wrong. There are dissenters who insist the world is flat, not a globe. You can even look out your window and see a flat world, but that is not extraordinary evidence. There’s more to it than that.

Imagine if an amateur historian publishes a book claiming that George Washington died before the American Revolution and that an impostor took his place and even became President. Imagine the evidence this book offers is not extraordinary, just a different interpretation. Now imagine that America believes this — and so we change all of our history books and rename countless places including Washington, D.C., and Washington State. Big changes, right? Now imagine that another amateur historian, with no more evidence than the first, publishes a book saying George Washington was always George Washington but that an impostor did replace Thomas Jefferson. And America believes this, and so, again, we change all of our history books and rename countless places. Then a third amateur historian, with no more evidence than the other two, publishes a book saying Washington and Jefferson were never replaced, but that an impostor did replace Abraham Lincoln.

You get the idea. It may sound ridiculous, but only because extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. With so much at stake, a little evidence isn’t enough. It must be absolute. Otherwise, any flimsy idea portrayed as new evidence could disrupt whatever you believe about almost anything. Our society could face constant turmoil, flip flopping with every silly claim. Fortunately, rigorous standards for evidence guard against this.

.

Thomas Jefferson

Jefferson himself explained it this way: “A thousand phenomena present themselves daily, which we cannot explain — but where facts are suggested … their verity needs proofs proportional to their difficulty.”

Apparently Washington believed the same. In retirement, Washington once received a book that claimed a secret group called the Illuminati sought to conquer the world and destroy Christianity through the lodge meetings of Freemasons. Washington, in a cordial reply, wrote that he, too, had heard ugly rumors about the supposed Illuminati, and although he himself was a Freemason himself, Washington said he hadn’t attended many lodge meetings. But, he added, “I believe notwithstandings, that none of the Lodges in this Country are contaminated with the principles ascribed to the Society of the Illuminati.” He also apologized that he would not have time to read the book.

Remember: Washington had been a spymaster — and to judge his agents’ reports, he had used critical thinking. To claim the Illuminati is conspiring to conquer the world through Freemason lodge meetings is an extraordinary claim. Washington did not consider mere rumors and a book to be extraordinary evidence. Not even close.

A… Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

A theory supported by evidence is better than a theory without evidence. But a theory by itself is still a theory — and someday, it might be proven. Lacking evidence today doesn’t mean the theory is false. It remains possible until it is directly disproven.

A theory supported by evidence is better than a theory without evidence. But a theory by itself is still a theory — and someday, it might be proven. Lacking evidence today doesn’t mean the theory is false. It remains possible until it is directly disproven.

Intelligence analysts and police detectives know that absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, for they face opponents who are actively trying to deceive them. Imagine that a notorious gangster is tried for murder, but the evidence against him is only circumstantial. The jury is instructed that if they have any reasonable doubt he committed the murder, they cannot vote to convict. So, in this scenario, the verdict is Not Guilty. But is it possible this gangster, acquitted for lack of evidence, did commit the murder? Yes. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. It is also possible that he didn’t do it, but the theory that he did remains possible until disproven. He may escape jail, but not suspicion.

One implication of this is beware who you trust. General Washington wrote, “There is one evil I dread, and that is their spies.” He wrote this because an absence of negative evidence led him to fully trust another American general, Benedict Arnold — that is until Arnold fled to the British, leaving behind evidence of treason. “Arnold has betrayed me!” Washington exclaimed. “Who can I trust now?” He did continue to trust people, but also learned that nobody is above suspicion.

Please remember this guideline is only part of a system for logical reasoning, not the entire system. It does not mean that, in the absence of evidence, anything you want to believe is always logical. I might believe in the existence of green cats with purple polka-dots. There is no evidence such cats exist and no definitive evidence they don’t exist — but that doesn’t mean it’s logical to believe they do exist.

S… Skepticism includes a willingness to risk being wrong.

George Washington

Mistakes happen, and sometimes even the best spies pass along inaccurate information. When the spies of General Washington made this mistake, some of them apologized. And if the mistake was honest, he was forgiving. To one agent he wrote: “[M]istakes of this kind are not uncommon and most frequently happen to those whose zeal and sanguineness allow no room for skepticism when anything favorable to their country is plausibly related.”

In other words, Washington urged skepticism. Skepticism includes a willingness to risk being wrong. If you value the truth more than your own ego, then you shouldn’t feel embarrassed when proven wrong. Just accept the latest facts and move on. Yet, some people cannot accept being wrong because they take it all far too personally. Nobody expects you to be right all the time, but they believe they must be. To them, being wrong represents failure — a deep personal failure — and their fear of that overwhelms them with dread, shame, and self-contempt. Emotionally, they cannot risk being wrong — and so they imagine they never are.

Skepticism is not the same as cynicism. A cynic tends to assume the worst no matter what — and no amount of contrary evidence can persuade a cynic otherwise. Some say the opposite of cynicism is naiveté. A naïve person tends to assume the best no matter what, and no amount of contrary evidence can persuade that person otherwise. Cynical and naïve people have something in common, don’t they? Both believe they’re right no matter what. Show them the very same evidence and each will interpret it to fit their own beliefs. They emphasize the parts they like and explain away what they dislike. They may even be quite smart intellectually, but neither one is open-minded because, emotionally, they cannot risk the idea of being wrong.

.

Benjamin Franklin

The skeptic, being neither cynical nor naïve, is willing to put aside old beliefs as new evidence becomes available. No less than Benjamin Franklin confessed that “Having lived long, I have experienced many instances of being obliged by better information or fuller consideration to change opinions even on important subjects, which I once thought right but found to be otherwise.”

Genuine skepticism requires a constant balance between being cynical and naïve because life experiences could push you to one extreme or the other. People often demand quick decisions and to follow the crowd — instead of pausing to ask the tough questions worthy of a skeptic and scrutinizing the answers carefully. Being a skeptic takes constant practice — or you’ll lose the habit, replaced by a dangerous assumption that you already know the important stuff.

So, from time to time, pause and ask yourself, am I genuinely skeptical? Have I become cynical? Or naïve?

To find the truth, you need to risk being wrong.

O… Opposite sources inform you of more than one side.

Joking about politicians can be fun, but please treat politics itself as seriously as a jury trial — because the results are just as real. In a jury trial, both sides are heard. It’s only fair, and common sense.

.

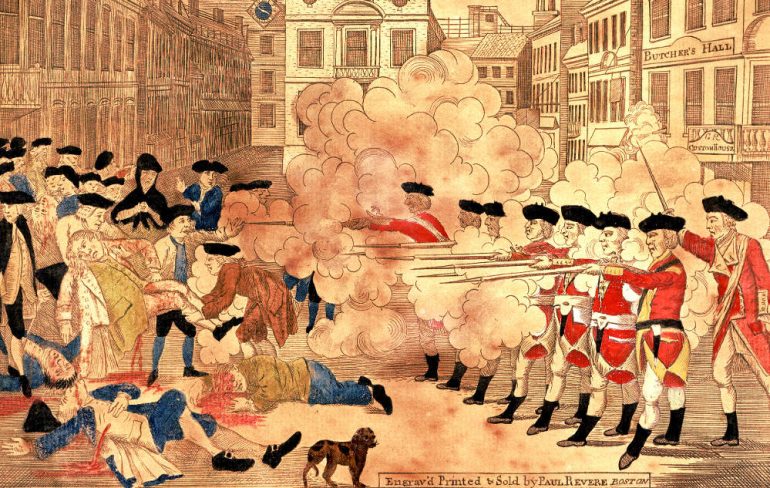

In Boston, in the year 1770, amid rising tensions before the American Revolution, a squad of British soldiers shot and killed several Bostonians in a dispute known as the Boston Massacre. The soldiers said an angry mob was throwing things at them and, afraid for their lives, they fired. They were charged with murder. The people of Boston were so outraged that only one lawyer agreed to defend them. This made him very unpopular, but he was determined that the soldiers get a fair trial.

That lawyer was John Adams, and he won the case by emphasizing reasonable doubt — the first time this term was used in a jury trial. Decades later, Adams considered his defense of those British soldiers to be one of his greatest achievements and a great service to his country. His wife, Abigail Adams, wrote, “I’ve always felt that a person’s intelligence is directly reflected by the number of conflicting points of view he can entertain simultaneously on the same topic.”

Little wonder Abigail married John.

.

Abigail and John Adams, in portraits painted during his Presidency

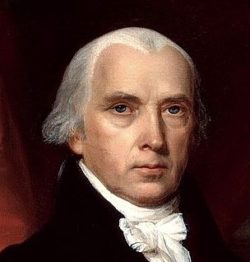

James Madison

Like in a jury trial, opposite sources inform you of more than one side. Today’s news media is notorious for its harsh criticisms and for being harshly criticized — but this isn’t new. James Madison, who drafted the U.S. Constitution, wrote, “To the press alone, checkered as it is with abuses, the world is indebted for the triumphs which have been gained by reason and humanity over error and oppression.”

Every Founding Father who later became President, including Madison, was harshly criticized by the press. Some of that criticism was even accurate, but how would you know if you don’t read it?

Just as we now read the Founding Fathers, they read Francis Bacon, a religious English philosopher who invented the modern scientific method we now call empiricism. For this contribution, Thomas Jefferson considered Francis Bacon as important as John Locke and Isaac Newton.

Francis Bacon

Bacon advised: “Read not to contradict and confute; nor to believe and take for granted; nor to find talk and discourse; but to weigh and consider.”

To follow that advice, never limit yourself to only one news source, because even a good news source narrows your perspective to whatever its editor considers important. News outfits actually compete, so let that competition inform you. Search the Internet using the phrase “List of major news websites.” You can also search “List of conservative news websites” and “List of liberal news websites.” But when you research political issues, please research both sides.

You can find several news sources on what’s called a news aggregation website, such as Google News, MSN.com, or Yahoo!. But beware of choosing articles from only those news sources you prefer, for all of them might lean towards the same political side. Read about the same topic using two or more articles, including one from the political opposite. Then look for gaps in how the topic is covered. Which facts does one article report but another does not? You might be surprised. And if an article says something extraordinary, remember that extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. So run an Internet search of that topic. Also, search the article’s exact headline, word for word, because another website may have posted something in response, either supporting the claim or debunking it.

A few websites perform fact-checking as a public service, including FactCheck.org, PolitiFact.com and Snopes.com. Sometimes even these sites are accused of bias, but they’re still worth reading because they explain how they investigate, what sources they use, and how they apply logic and critical thinking.

Some people resist any political opinion not from their own party. Imagine Communists who listen only to Communists. Yet, there are Republicans who listen only to Republicans, and Democrats who listen only to Democrats. Why isolate yourself? Afraid of being brainwashed by so-called enemy propaganda? Give yourself some credit! Every day we’re bombarded with propaganda: we call it commercial advertising. Ads try to persuade you to buy something — but no ad can force you to. In politics, whether you lean Republican or Democrat, you as a citizen have a duty to learn the other party’s perspective.

Here is a reason why. The voting population of the United States is approximately 300 million people. About one-third are Republicans, one-third are Democrats, and one-third are Independents. Do you really believe that no good ideas can be found among 100 million people, or more, merely because their political party is not yours? What are the odds? Count to 100 million and you’ll soon discover how large that number is. When our politics suffer extreme partisanship, and nastiness, and an obsession against compromise, the results damage our country. And any partisan gains will not last because, eventually and inevitably, elections will flip power back and forth.

Several Founding Fathers warned us of this.

John Adams

John Adams lamented: “There is nothing which I dread as much as a division of the Republic into two great parties, each arranged under its leader, and concerting measures in opposition to each other. This, in my humble apprehension, is to be dreaded as the greatest political evil under our Constitution.”

Likewise, George Washington warned: “The common and continual mischiefs of the spirit of Party are sufficient to make it the interest and duty of a wise people to discourage and restrain it.”

As for propaganda, I’ve read actual enemy propaganda for more than 30 years — Communist propaganda, the terrorist propaganda of ISIS and al-Qaida, even old Nazi propaganda — and I’ve never been brainwashed, because that isn’t how brainwashing works. Brainwashing tries to limit your sources to only one perspective — a perspective not treated with skepticism nor critical thinking. Indeed, by not practicing critical thinking, you can actually brainwash yourself by isolating yourself from any perspective you disagree with. This phenomenon is called “living in a bubble” or “in an echo chamber.”

But propaganda can reveal how its proponents think and the deceptive claims they use. You won’t be brainwashed if you remember that propaganda exists to persuade, not necessarily to inform. Whatever it claims to be a fact, don’t believe it until you confirm it independently. Opposite sources are vital for that. A major reason why terrorist propaganda online has radicalized so many young people, especially adolescents, is because they didn’t use critical thinking — typically because nobody taught them how to.

Opposite sources are especially important if you’re among an estimated 20 percent of Americans sometimes called news junkies. News junkies follow politics so closely that they know the major issues and often discuss them. News junkies play an important role in society because their views and explanations help to inform and influence friends and family. But when your opinion on a major issue is widely listened to, you have a responsibility to learn the complete facts and both sides, not merely what one side says about the other side. You don’t have to like both sides, but use multiple sources, including opposite sources.

.

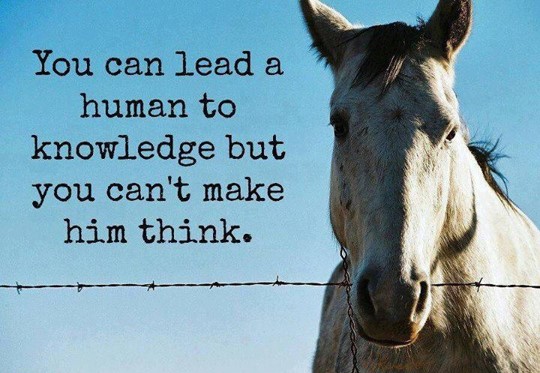

If there is any exception to using opposite sources, it involves something that isn’t a news source at all, but is too often treated as one: a meme. On social media the typical meme shows an emotional picture or two, emphasized by a very short, politically-slanted message. I’ve seen memes misrepresent or even lie about what their pictures really show; and I’ve read some messages so distort the facts, you could find more accurate information on a bumper sticker. Imagine a political cartoon. Would you get most of your news from that? Would you want a jury trial to decide every case based on what little information can fit into a political cartoon? A meme is the blogger’s equivalent of a political cartoon — but instead of offering a clever drawing, the blogger portrays his opinion as a fact. Yet, because it provides so little information, any comparison between politically opposite memes is not likely to make you much smarter — unless you’re trying to become an expert on memes!

If there is any exception to using opposite sources, it involves something that isn’t a news source at all, but is too often treated as one: a meme. On social media the typical meme shows an emotional picture or two, emphasized by a very short, politically-slanted message. I’ve seen memes misrepresent or even lie about what their pictures really show; and I’ve read some messages so distort the facts, you could find more accurate information on a bumper sticker. Imagine a political cartoon. Would you get most of your news from that? Would you want a jury trial to decide every case based on what little information can fit into a political cartoon? A meme is the blogger’s equivalent of a political cartoon — but instead of offering a clever drawing, the blogger portrays his opinion as a fact. Yet, because it provides so little information, any comparison between politically opposite memes is not likely to make you much smarter — unless you’re trying to become an expert on memes!

N… Nothing happens in isolation. Consider the context.

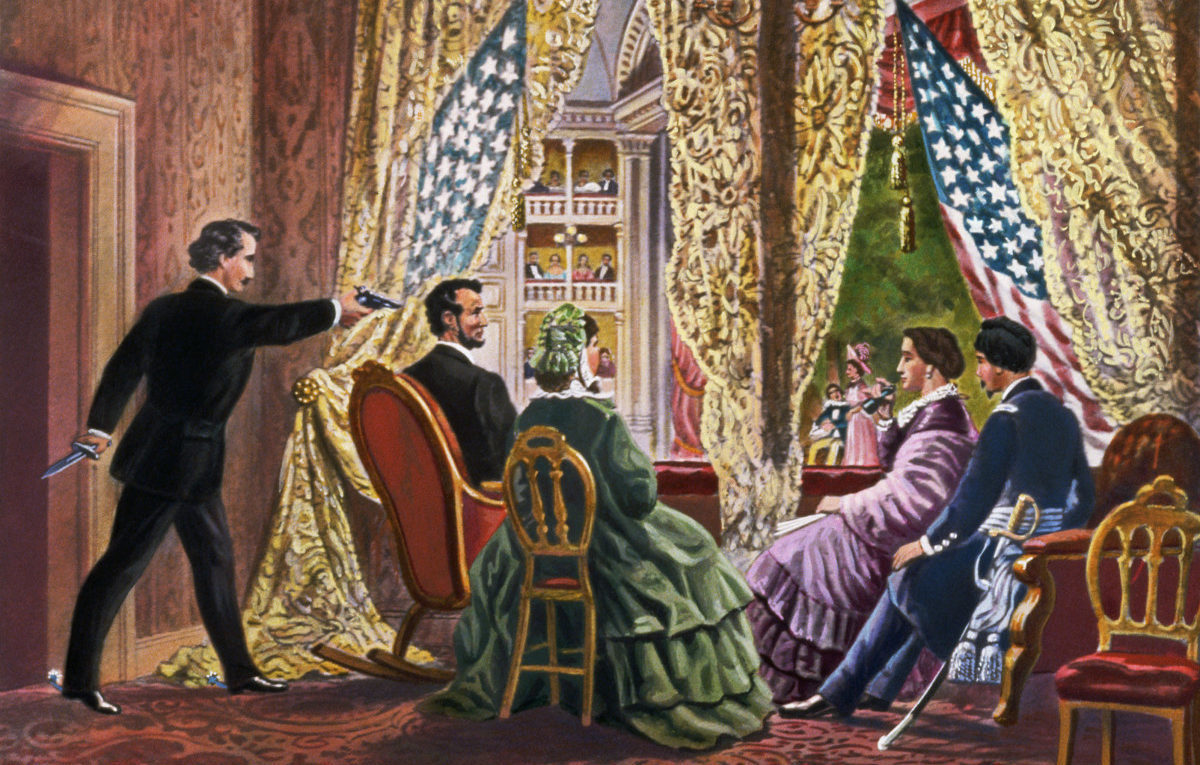

This is where most conspiracy theories break down. Not all do, because some conspiracies are real. The assassination of President Abraham Lincoln was part of a conspiracy, one which also targeted Lincoln’s Vice President and Secretary of State. But on the Internet, most conspiracy theories make extraordinary claims without extraordinary evidence — and in some cases, without much evidence at all.

Nothing happens in isolation. The assassination of Lincoln occurred in the context of the American Civil War — but at the war’s end, when precautions for his security were very lax. Given these facts, it’s not so surprising that a few supporters of the Confederacy could assassinate him. But if you didn’t know that context, you might assume that only an inside job could assassinate the President of the United States.

Considering the context also means recognizing how easily things can go wrong, especially in a conspiracy. In Nazi Germany, several German officers secretly opposed to Hitler made several dozen plots to assassinate him. Several dozen — and they all failed, always because some minor detail or variable went wrong. This problem is so common that the American military teaches an acronym for making plans: K-I-S-S — Keep It Simple, Stupid — because a plan with too many variables contains too much risk. Remarkably, those German officers against Hitler knew how to run a military operation, knew to keep it simple, and yet their many plots still failed.

Variables matter. Imagine driving to a place you’ve never been to before, on roads you’ve never driven before, using a map you’ve never seen before. Which route would you prefer: simple or complicated? The simple route is usually better because it contains fewer chances to make a wrong turn. In other words, fewer variables. Every variable adds not just an additional risk but an entire set of risks, a variety of possibilities. In other words, every additional variable multiples the risks.

.

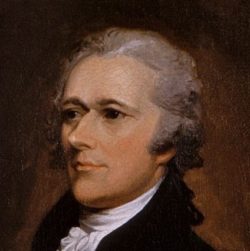

Alexander Hamilton

This is known as Ockham’s Razor, an idea named for William of Ockham, a Christian monk. He popularized the idea that if you can reach the same result with fewer variables, then cut out the unnecessary variables. Cutting down to the most efficient minimum reduces the chances of a different outcome. Alexander Hamilton noted, “In disquisitions of every kind there are certain primary truths, or first principles, upon which all subsequent reasoning must depend.” One of those first principles is Ockham’s Razor.

Many conspiracy theories violate Ockham’s Razor to an extraordinary extent.

I’ll use one involving 9/11. History records that on September 11, 2001, terrorists hijacked and crashed four airliners into the Twin Towers, the Pentagon, and a field in Pennsylvania after passengers on the fourth plane fought back. But some conspiracy theorists claim that, the night before, American secret agents snuck into the Twin Towers and planted explosives throughout. They claim the whole event was staged to terrify the American public into giving more power to the U.S. Government to wage war in the Middle East.

Leaving aside the fact that Afghanistan is not in the Middle East, let us consider this theory that secret agents rigged the Twin Towers with explosives. If true, it would rank among the biggest and most complicated covert operations in the history of the world, performed entirely illegally. It would involve hundreds, even thousands of co-conspirators secretly breaking into the Twin Towers, at night, rigging almost every floor with explosives without being noticed by any security guards or any security cameras, all in order to deceive the world that crashing airliners alone caused the damage.

Leaving aside the fact that Afghanistan is not in the Middle East, let us consider this theory that secret agents rigged the Twin Towers with explosives. If true, it would rank among the biggest and most complicated covert operations in the history of the world, performed entirely illegally. It would involve hundreds, even thousands of co-conspirators secretly breaking into the Twin Towers, at night, rigging almost every floor with explosives without being noticed by any security guards or any security cameras, all in order to deceive the world that crashing airliners alone caused the damage.

How many variables — and how many risks multiplied by each variable — does this conspiracy theory have? So many, it boggles the mind. How many secret agents must be bribed or sworn to secrecy, for life, to perpetrate the mass murder of fellow Americans? How many security guards must look the other way? What about the janitors, cleaning crews, and anyone else in the Towers that night? All sorts of problems could spoil this plot, including any bomb residue found in the rubble, any clues left elsewhere, any whistle-blowers leaking the story, or any investigative journalists looking for the scoop of a lifetime. If you were asked to participate in the plot, would you trust it?

Consider Ockham’s Razor. Why would the conspirators go to all this trouble? Why not just persuade a few stooges with suicidal thoughts to become hijackers and crash airliners into the Twin Towers? Even this alternative makes some extraordinary claims without evidence, but at least it doesn’t include the enormity of risks inherent in those other theories.

Nothing happens in isolation. What would the conspirators gain? What did they stand to lose? They could not know in advance if their incredibly complicated plot would succeed. Given the enormous risks involved, wasn’t there an easier way? In the military especially, experienced leaders know that no matter how good the plan, reality is surprisingly unpredictable. You can guess in advance, but only guess. So why take the risk? The biggest risk of their lives? The opportunity to become mass murderers of fellow Americans, risking public exposure and eternal shame? Any of them could become a whistle-blower of this enormously illegal plot and, by exposing it, be a hero. Which opportunity would you choose?

.

Context includes implications. If this conspiracy theory were true, what else would have to be true? It would mean that a new President, in office less than a year, somehow managed to persuade, secretly, thousands of people throughout the U.S. Government, including in the FBI, the State Department, the Armed Forces, and top leaders in both houses of Congress, indeed from both political parties, to become accomplices to the most monstrous crime in American history, just to justify more military action in the Middle East which the President could already order. (He didn’t need this plot.) It would mean that those thousands of people, many with long careers in public service including in the military, suddenly chose to betray the public trust — on a massive scale. It would mean no whistle-blowers among them. It would mean the major news media failed to uncover the scoop of the century and, since 9/11, has not found enough evidence to question the accepted story. And it would mean that the conspiracy theorists themselves are probably part of the plot — because why else would a government capable of staging this enormous sham allow anybody to speak out, leaking embarrassing information and raising popular suspicions?

Context includes implications. If this conspiracy theory were true, what else would have to be true? It would mean that a new President, in office less than a year, somehow managed to persuade, secretly, thousands of people throughout the U.S. Government, including in the FBI, the State Department, the Armed Forces, and top leaders in both houses of Congress, indeed from both political parties, to become accomplices to the most monstrous crime in American history, just to justify more military action in the Middle East which the President could already order. (He didn’t need this plot.) It would mean that those thousands of people, many with long careers in public service including in the military, suddenly chose to betray the public trust — on a massive scale. It would mean no whistle-blowers among them. It would mean the major news media failed to uncover the scoop of the century and, since 9/11, has not found enough evidence to question the accepted story. And it would mean that the conspiracy theorists themselves are probably part of the plot — because why else would a government capable of staging this enormous sham allow anybody to speak out, leaking embarrassing information and raising popular suspicions?

With so many variables — and with so many risks, it boggles the mind — isn’t this conspiracy theory a bit much to swallow?

Since absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, you might wonder if some conspiracy theories are impossible to disprove. To some extent, perhaps — but they’re already unlikely because extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. Ockham’s Razor applies to odds as much as to variables. Since more variables actually multiplies the risks, this raises the odds against any particular outcome. It’s like trying to win a lottery against a million other players instead of against a few dozen. Any theory which violates Ockham’s Razor so extremely raises the odds against that theory working in practice. Odds this extreme might as well be impossible.

Still, mysteries intrigue people. If a supposed mystery exists, some conspiracy theorist may offer a theory. But it’s rarely a simple explanation befitting Ockham’s Razor. No, it’s usually an extremely complicated explanation which, if true, would create numerous clues which somehow are never found. It leaps to an extreme conclusion by ignoring mundane facts.

Indeed, the supposed mystery may not be so mysterious after all. In the case of 9/11, a supposed mystery is that the steel beams of the Twin Towers could not melt at the fire temperatures the Towers experienced. Being an engineering problem, this sounds like decent evidence — until you realize it assumes that only melted beams could collapse the Twin Towers — or else, explosives. But the fact is when steel is heated red-hot, it loses most of its strength long before it melts. Watch a blacksmith bend a red-hot steel bar without melting it. No mystery. The steel beams of the Twin Towers didn’t melt and didn’t have to. They simply bent and gave way. Hence, the collapse.

Indeed, the supposed mystery may not be so mysterious after all. In the case of 9/11, a supposed mystery is that the steel beams of the Twin Towers could not melt at the fire temperatures the Towers experienced. Being an engineering problem, this sounds like decent evidence — until you realize it assumes that only melted beams could collapse the Twin Towers — or else, explosives. But the fact is when steel is heated red-hot, it loses most of its strength long before it melts. Watch a blacksmith bend a red-hot steel bar without melting it. No mystery. The steel beams of the Twin Towers didn’t melt and didn’t have to. They simply bent and gave way. Hence, the collapse.

I won’t debunk every 9/11 conspiracy theory, but there are websites which do and which debunk other conspiracy theories. To find them on the Internet, search “Debunking conspiracy theories” and likewise the topic, in this case “9/11.” Other topics can include “Moon landings”, “vaccinations” and “Sandy Hook massacre.”

.

Thomas Jefferson

In conclusion, critical thinking requires skepticism, logic, Ockham’s Razor, and perhaps most importantly, curiosity. Be curious about everything. That doesn’t mean be reckless, but beware of your assumptions — for unlike children who are naturally curious, too many adults assume that they already know everything they need to know about everything. So they shut down their curiosity and shut off their willingness to use critical thinking. This is incredibly dangerous because it is incredibly gullible. Cynical or naïve, it doesn’t matter — because con artists can exploit that. But it’s tougher to deceive a skeptic who keeps asking questions, who notices when the supposed answers lack substance, and who gets information from a range of sources. That is critical thinking.

Critical thinking is neither liberal nor conservative. It is not evil, nor anti-religion, nor anti-science. It is simply a smart way of using common sense. Anyone can practice critical thinking and we all should — because the future of our democracy depends on it.

For as Thomas Jefferson warned, “If the nation expects to be ignorant and free, in a state of civilization, it expects what never was and never will be.”