The following blog post was produced by Reginald Dipwipple, Secret Agent Extraordinaire. (As in, it’s extraordinary that this guy is a secret agent.) He is the author of the pseudo-biographical novel, Tongue-Tied With Stomach Knots: An Enlightened Comedy, among other writings of dubious distinction.

Please forgive us for posting this, but we took pity on a struggling author. (Yes, that pity was misplaced.) The Donovan Institute would issue a disclaimer, but we cannot believe that anybody takes this stuff seriously.

.

IMINT is the acronym for Imagery Intelligence.

When this term is used in casual conversation, it is usually shortened to a single word: imagery. The word sounds very technical (one of its charms), but it’s just a fancy way of saying intelligence collected from photographs. You might think that sexy photographs are found only in glossy magazines, but spies know of another source: aerial reconnaissance — photos taken by a spy plane or a spy satellite.

That said, what a spy considers “sexy” may have nothing to do with sex. (It also means the guy needs to get a life.) In the U.S. Army and Marine Corps, the word reconnaissance is sometimes abbreviated as recon, whereas in the Air Force the abridged version is recce. The latter is pronounced WRECK-kee.

“That sounds a bit ominous.”

Yes, it can be. Once upon a time, the French Army fought and won the Battle of Fleurus through the help of an observation balloon. That was in 1794. Now think about that. The practice of aerial reconnaissance is that old.

— Monsieur, I want you to undertake some aerial reconnaissance. Up, up and away in my beautiful balloon.

— Aerial reconnaissance? Pardon Monsieur, but why must I reconnoiter the air? Is it going somewhere?

— Uh, no.

— Are the troops experiencing gastrointestinal problems? I did warn you about all that fatty French cuisine.

— No, Monsieur, everyone is fine, merci. But from our balloon I want you to observe the movements of the enemy. Observe them from up in the air!

— Up in the air? Do you mean — IN THE SKY?

— Calm yourself, Monsieur, this balloon really does fly. One of the first balloon flights was witnessed by the American ambassador to France, Benjamin Franklin. It is quite safe.

— Then send Doctor Franklin! Or just you!

— Monsieur, alas, I cannot go. At stake are liberty, equality, fraternity! If I go, who will browbeat the peasants?

— But Monsieur, up in that balloon, I will be shot at by the enemy’s l’bang-bangs and l’boom-booms!

— L’what and l’what? Monsieur, if you please, it is a semantic calamity to speak pseudo-French. You sound ridiculous.

— Comme vous voulez. Je crois que vous êtes un imbécile! ET VOUS SENTEZ DĔGOUTANT!

— You too! And don’t get so personal! Listen, Monsieur, up in the air, you will appear but a tiny speck within a basket petite. The musket balls of the enemy will never hit you!

— Never hit ME? What about the BALLOON? It will experience l’grand pop! Which will render me l’deaf! Followed by l’yikes! And then l’crunch!

— Oh no, Monsieur, not l’crunch. Maybe l’splat, but not l’crunch. UUUUGH! NOW YOU’VE GOT ME DOING IT! Monsieur, for the sake of the reader, SPEAK ENGLISH! Where is your spirit of high adventure?

— Well grounded! Where I want it to stay!

— Monsieur, do this for France! For liberty, equality, fraternity! For quiche and escargot!

— For escargot? Do this for snails? You’re going to cover my quiche pie with snails? Delicious! But I do have one question.

— Anything, Monsieur. No, we do not offer flight insurance.

— No, Monsieur, not that. But what do I do for a latrine?

— Ah! Oh, I didn’t think of that. Hold it. Diligently. Then warn us.

Well, that famous flight over Fleurus, followed by its fantastic finale, fabulously feted the French. What is unfathomable, however, is that this famous flight failed to further flying as a fundamental factor favored by fighting forces. Quite fantastically, frequent flying was soon forgotten. Not until seven decades later, during the American Civil War, did the business of battlefield ballooning rise again.

.

The U.S. Army Balloon Corps. Horses and wagons not necessarily included.

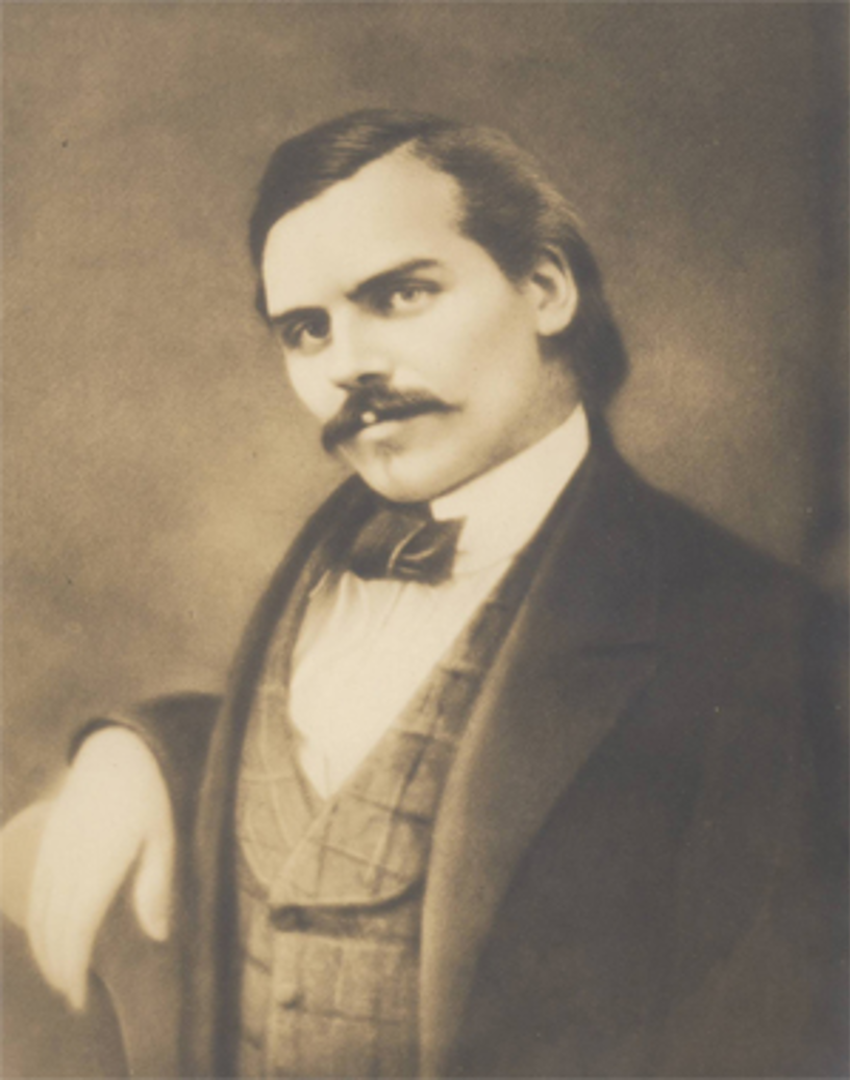

Thaddeus Lowe. Balloonist spook and target of the enemy (which included Federal bureaucratic birdbrains).

In 1861, the head of the U.S. Army’s Balloon Corps was a balloon designer named Thaddeus Lowe. (Interesting name.) Lowe reached the lofty height of President Lincoln’s personal support when Lowe held a sightseeing demonstration from his own favorite balloon, which soon became the Army’s favorite balloon: the Enterprise. (Yes, it’s true, Star Trek fans.) Later, Lowe directed cannon fire down upon Confederate encampments, even as the Rebel soldiers there were celebrating the promotion of their commander, General “Jeb” Stuart. Thoroughly annoyed by this interruption, they soon gave Lowe an eminent distinction: he quickly became the most shot-at man in the Union Army. And never hit. (Altitude helps.)

Lowe did insist that his balloons be tethered tightly to prevent them from drifting over enemy lines. Otherwise, if the Confederates ever shot one down, the Rebels might capture the balloon’s lone passenger and, because the guy was a civilian, execute him as a spy. Talk about a downer.

Yet in spite of Lowe’s lofty laborings, he and his Balloon Corps eventually found themselves beaten low by the Union’s bumbling bureaucrats, along with bombastic bystanders who besmirched the balloonists as basically buffoons boasting too much hot air. When Lowe dared to get sick (albeit, only malaria), he returned from the hospital to discover that his Balloon Corps had been stripped of its horses and wagons and, later, that his own pay had been dramatically reduced. He resigned in disgust.

Soon thereafter the Balloon Corps was disbanded.

Thrilling the Confederates.

Respectfully (because all my readers deserve respect),

Reginald Dipwipple

Secret Agent Extraordinaire

.

Israeli soldiers prepare a spy balloon for flight.