Would you believe there is still a place on the planet named East Berlin?

Really. And it isn’t in Germany.

Nope, the place is located in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Literally named East Berlin, it is a borough of Pennsylvania’s Adams County. The county does not have a West Berlin.

You can’t make this stuff up.

Alright then, let us remember what life was like in Communist East Germany.

“Hello, Comrade Leader? This is the chief of the infallible Stasi secret police. Comrade Leader, I’m telephone you because our impregnable Stasi headquarters has been burglarized!”

“Burglarized! Was anything stolen?”

“Yes, Comrade Leader! The results of next month’s elections!”

(Incidentally, the British prefer to spell their spy agency as MI6, not MI-6. They prefer to, that is, until some Americans pronounce it as M-sixteen and wonder why the Brits named their spy agency after an American rifle. To avoid confusion, we’re going to use MI-6.)

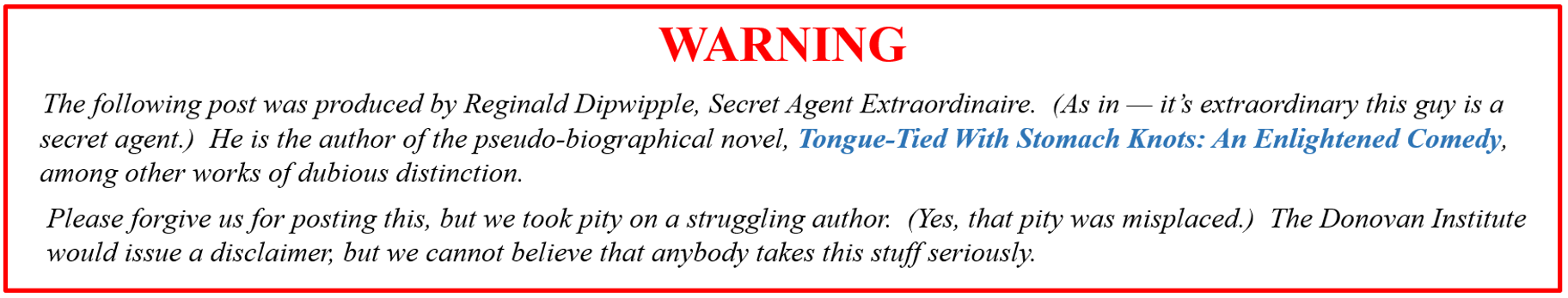

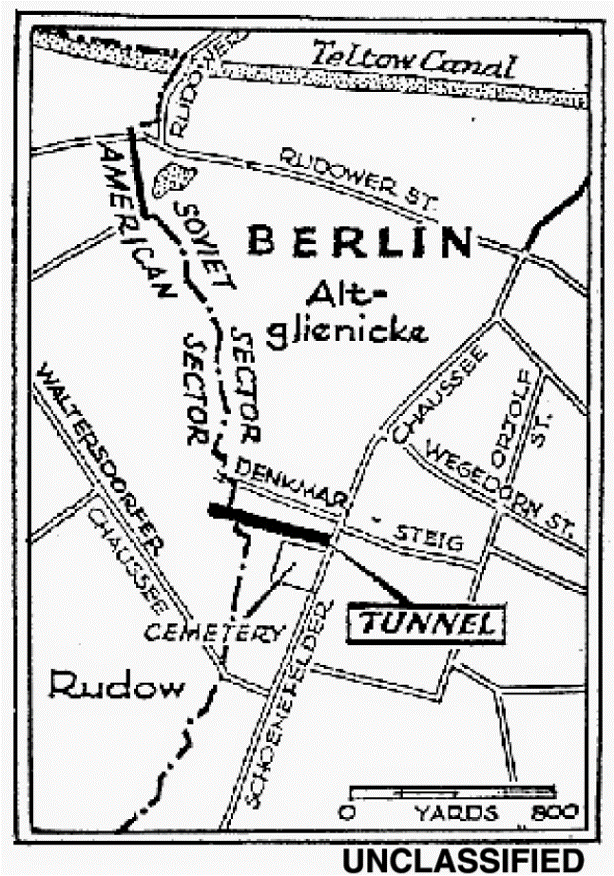

The operation was not as simple as just grabbing a shovel and digging. Everything had to be done secretly and silently. The particular spot where the phone cables were buried (which the CIA learned from some sympathetic East Germans) was only a meter below the surface, right next to a major highway. The Americans, who did most of the digging, had to tunnel very closely under those cables while still maintaining enough of a roof so that any passing Communist truck would not tumble through and crush the tunnel spies.

.

“Hello, Yanks! I’m just visiting from MI-6. How are you chaps coming along? You know, this tunnel reminds me of the Great Escape, when a motley bunch of British prisoners of war tunneled out of a Nazi prison camp. Except yours is tunneling the wrong way.”

“Yeah, because we’re tunneling into Commie East Berlin!”

“No, because you’re tunneling the wrong way. Two more feet and you’ll hit France. Yanks, try a compass.”

According to the CIA’s official history of the operation, the spies did encounter “an unanticipated, messy problem” when they mistakenly tunneled into their own sanitation system.

Yuck.

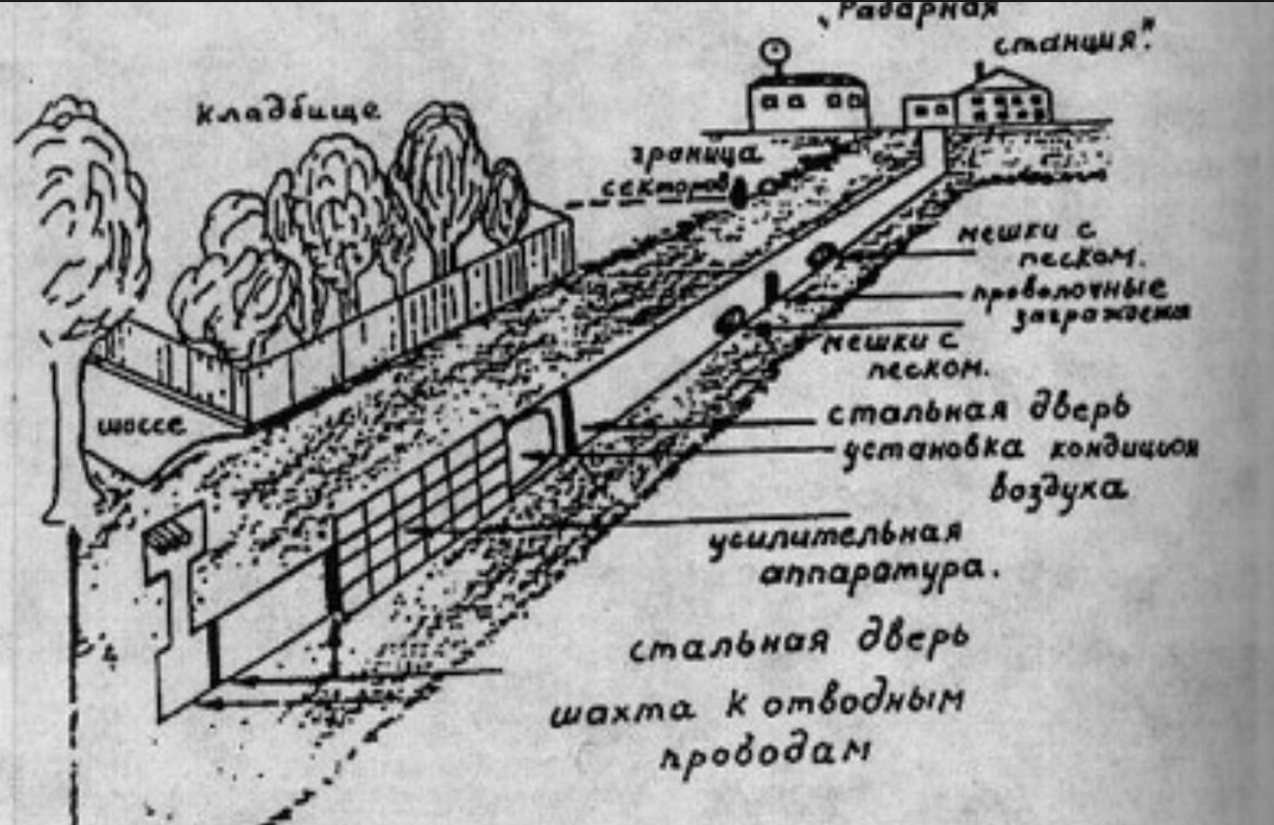

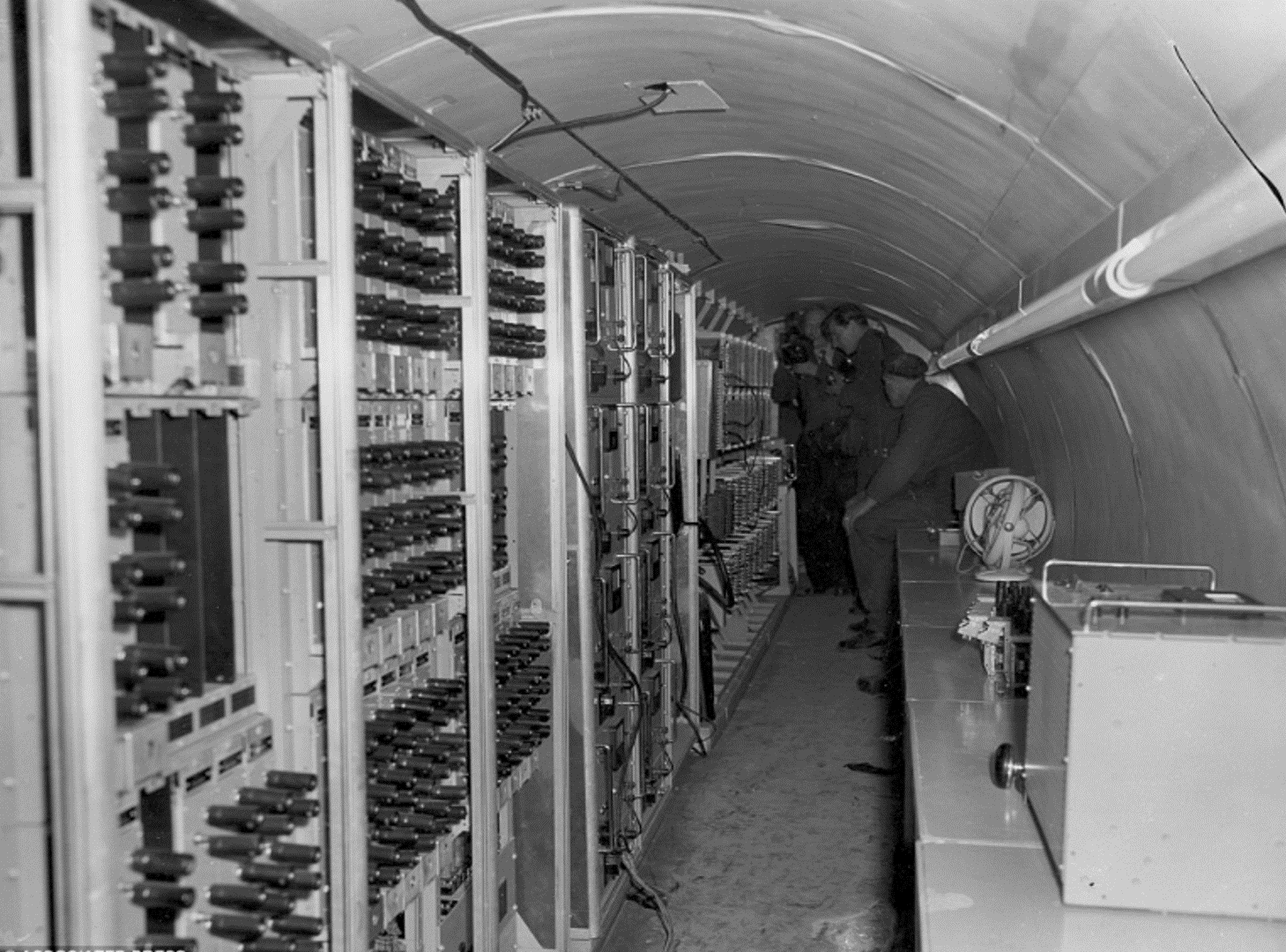

Otherwise, things went well. With remarkable quiet, the underground spies extracted 3,100 tons of soil, enough to fill more than twenty American living rooms up to the brim. The tunnel reached a quarter-mile in length, reinforced with 125 tons of steel liner plate. To conceal any hint of digging, not even on their clothes, they installed automatic washers and dryers for their clothes at the secret entry point in West Berlin. In fact, not a single cubic foot of soil ever left the entry site; it all got piled into the basement of an adjacent warehouse. Metal parts for the tunnel were first sprayed with a rubberized compound to eliminate any clanking; then they were taken inside and assembled. Sandbags were piled along the walls to help muffle any noise and serve as shelves. Recording equipment was brought in. For added security a heavy steel door was installed on the West Berlin side, while underneath East Berlin a hidden microphone was inserted into the tunnel roof. The microphone was so receptive that it picked up the footsteps and conversations of the Stasi guards patrolling above.

Otherwise, things went well. With remarkable quiet, the underground spies extracted 3,100 tons of soil, enough to fill more than twenty American living rooms up to the brim. The tunnel reached a quarter-mile in length, reinforced with 125 tons of steel liner plate. To conceal any hint of digging, not even on their clothes, they installed automatic washers and dryers for their clothes at the secret entry point in West Berlin. In fact, not a single cubic foot of soil ever left the entry site; it all got piled into the basement of an adjacent warehouse. Metal parts for the tunnel were first sprayed with a rubberized compound to eliminate any clanking; then they were taken inside and assembled. Sandbags were piled along the walls to help muffle any noise and serve as shelves. Recording equipment was brought in. For added security a heavy steel door was installed on the West Berlin side, while underneath East Berlin a hidden microphone was inserted into the tunnel roof. The microphone was so receptive that it picked up the footsteps and conversations of the Stasi guards patrolling above.

“Hey, Comrade, what are you thinking about?”

“Nothing, Comrade. Same as you.”

“Oh? In that case — you’re under arrest!”

The Stasi patrols became an even greater concern during the winter. That is because the tunnel’s amicable air temperature created the unintentional effect of warming the ground above it. Think about that for a moment. What if the Stasi guards, trouncing through the snow, suddenly discovered a mysteriously frost-free path, a quarter-mile long, emanating from West Berlin? The spies’ solution was to equip their tunnel with a better refrigeration system. (Can you believe it? The Cold War really was fought with refrigerators.)

In March 1955, the tunneling spies reached their objective and tapped into three Soviet military telephone cables. Then, for almost a year, the spies recorded 40,000 hours of phone conversations and six million hours’ worth of teletype messages. The haul included 443,000 fully transcribed conversations, including discussions of the latest developments in Soviet nuclear weapons research, detailed information about Soviet military units, and even disagreements between the Soviets and East Germans over what to do about that embarrassing blemish upon the workers paradise, West Berlin.

Nothing is forever. The spies knew that someday the phone cables would require some routine maintenance — and then the Communists would discover the tunnel. That happened in April 1956, when a team of probing Soviet and East German engineers began to wonder what they had just unearthed. Meanwhile, the alert American spies rapidly packed up that day’s tape recordings and slipped away, closing the steel door behind them. The Communists burrowed into the eastern side of the tunnel. When they explored it, they were flabbergasted.

“What a filthy trick!”

Yes, somebody actually said that. We know because the hidden microphone recorded it. The enraged Communists walked all the way to the steel door. Behind it lay West Berlin. Next to the door they found a sign declaring in English, German and Russian: “Entry Prohibited — by order of the American Commander.”

The Communists had gotten snookered. And they didn’t like it. Almost never did the Soviets deign to hold a press conference, but this time they did. They denounced the whole operation and even gave public tours of the tunnel. Some 50,000 ordinary East German visitors gawked at it. And at the Soviets’ invitation, so did liberal Western journalists. The journalists were flabbergasted, dumb-founded, overwhelmed with emotion.

They loved it.

“You Communists got snookered! Ha ha! And the CIA is not as incompetent as we thought it was! Yeah!”

Not the message the Communists intended. Their embarrassment erupted in cheers and laughter in the corridors of the CIA and MI-6.

There was only one problem: the CIA and MI-6 had gotten snookered. And they didn’t know it.

You see, the KGB actually knew all about the tunnel, even before it was built, because the KGB had a spy inside British Intelligence.

.

His name was George Blake. Blake had been briefed in advance about the planned Operation Gold and he duly told his Soviet handlers. But the KGB had a problem: they considered Blake to be such a valuable spy, they reasoned they could not disrupt the tunnel without alerting MI-6 and the CIA that a traitor lurked in their very midst. What to do?

Why not insert false information into the tapped phone cables? Maybe, or maybe not. Consider the task of having to forge at least 443,000 conversations and six million hours’ worth of teletype messages. For any fake information to be believed, it must be convincing — which meant a great many pieces of information, and even pieces of pieces derived from more pieces, all had to conform to whatever genuine information the CIA and MI-6 could confirm using their other spies. For such an enormous and complicated deception, why not use a computer? Well, back then a Communist computer was little more an abacus.

So what did the KGB do?

A Soviet officer inside the discovered tunnel.

(Is he price shopping for spy gear?)

Nothing. They told nobody. And both the Soviet Army and the Stasi got snookered. Only after Blake transferred to another MI-6 section and after heavy rains had hammered Berlin could the Communists afford to “check” their phone cables for any natural damage without raising any spy suspicions.

So, who got snookered? Everybody! And everybody got something.

The CIA and MI-6 got massive amounts of valuable military data, plus the public embarrassment of the Communists — and, a bit later, the sly satisfaction of knowing the KGB let them get away with it all.

The KGB got to preserve their MI-6 spy, George Blake. He later escaped to the Soviet Union.

And even the Soviet Army and the East German Stasi got something: they got the chance to complain to the KGB.

“You jerks! You rank rampallian hedge-pigs! You Izmenniki and Dummköpfen! WHOSE SIDE ARE YOU ON?”

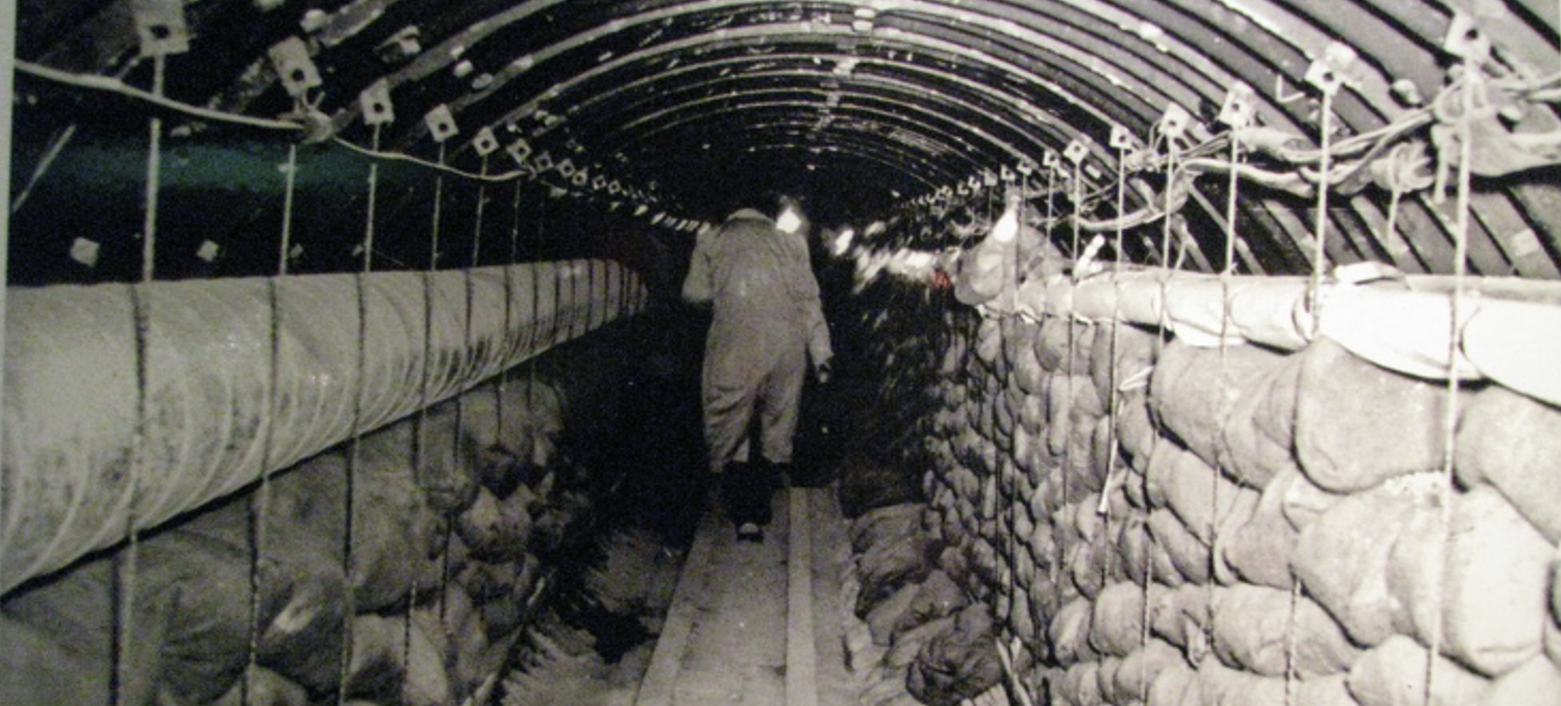

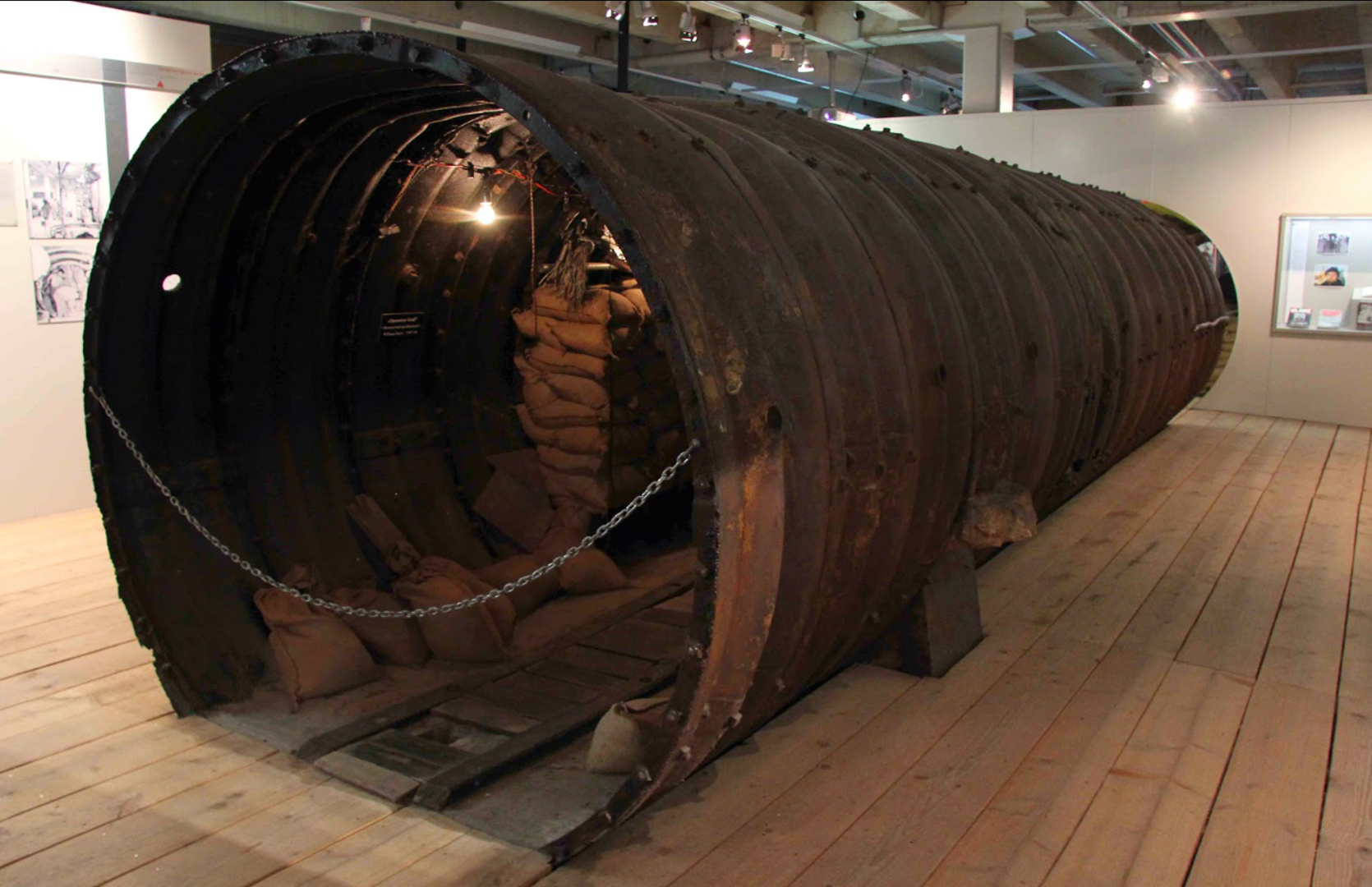

Finally, there are today’s Germans, East and West, who now live together in a united Germany full of democracy and free enterprise and with far fewer Trabants stinking up the place. Today’s Germans got the Berlin tunnel itself. It has since been dug-up and moved to a museum where it is still a tourist attraction.

Respectfully (because all my readers deserve respect),

Reginald Dipwipple

Secret Agent Extraordinaire

.

After the tunnel was discovered, the Communists posted guards inside.

No light at the end of this tunnel.

.

A portion of the Berlin tunnel today, dug-up and now in a museum.