>

Do you know that famous line from the American Declaration of Independence? The sentence that begins “We hold these truths to be self-evident…”?

.

You do?

Good.

Who wrote it?

The answer is — Thomas Jefferson.

Did you assume this was a trick question?

Gosh, you’re paranoid. I admire that.

Yes, it was a trick question — because the truth is Thomas Jefferson did not write that famous phrase.

Or at least not all of it.

In the original draft, Jefferson scribbled the words, “We hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable.” Later, however, the last three words were replaced with just one word: self-evident.

Guess who made that editing change?

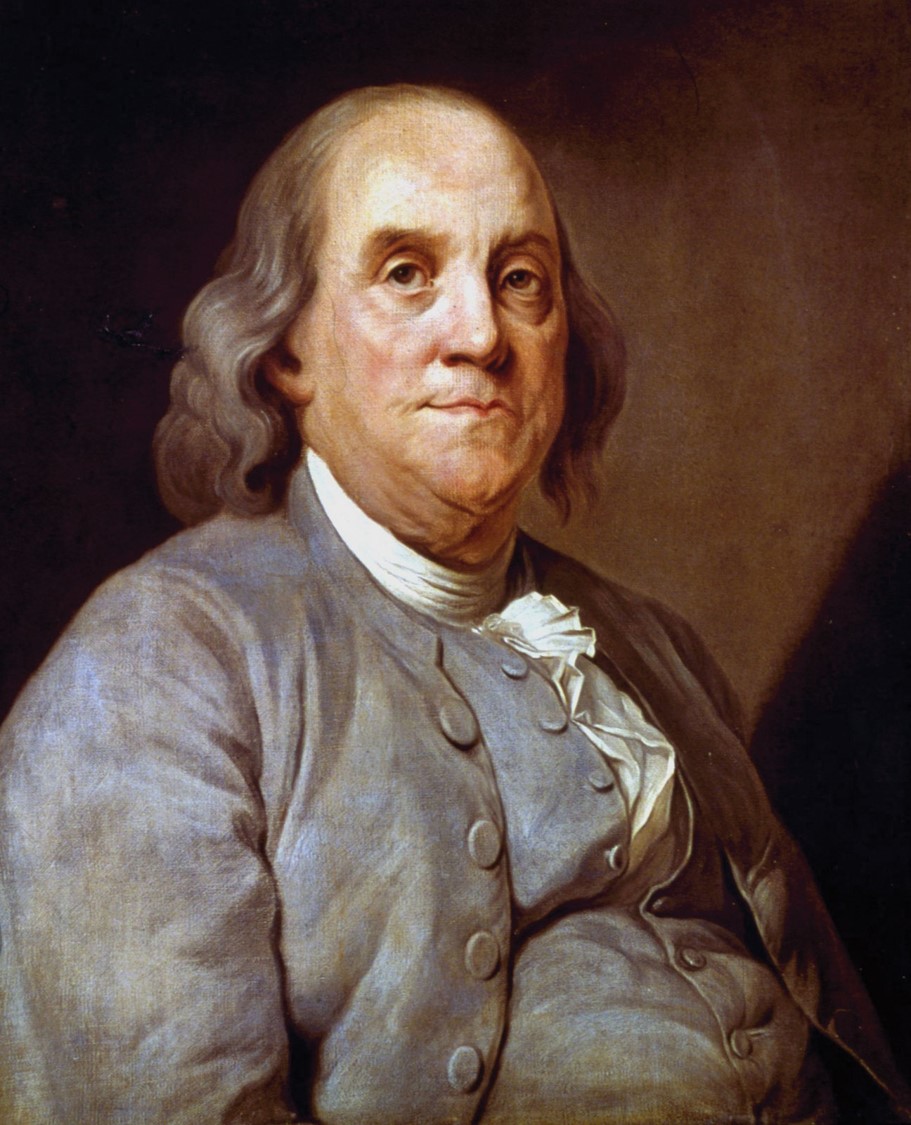

Benjamin Franklin.

I just thought you would like to know.

.

Our Man in Paris.

In the words of Sir Henry Wotton, “An Ambassador is an honest gentleman sent abroad to lie abroad for the good of his country.”

During the American Revolution, the American Patriots had sympathizers even in London itself, and that number increased as information about the war became increasingly gruesome — and increasingly unflattering to the King. For example, Londoners were shocked to read in a Boston newspaper that the Royal Governor of Canada had paid bounties to his Indian allies for every American scalp they sliced off. The newspaper reported that the scalps included those of women and children.

On another occasion, London readers were infuriated by a letter (reprinted in the newspapers) which was addressed from a Hessian Prince to the commander of his mercenary troops in America. The Prince’s letter complained that his British clients were under-reporting exactly how many Hessian mercenaries were getting killed in America. His was a very serious complaint, for according to the terms of his mercenary contract with the British, the Prince was to be paid (“reimbursed”) for every death his soldiers suffered. Furthermore, because the Prince was paid more for the mercenaries who got killed instead of those merely wounded, his letter ordered his surgeons in America to let the wounded Hessians die. That is, unless a speedy recovery was expected, because then the guy could return to combat duty. After all, business is business.

When the kindhearted Benjamin Franklin read of these terrible atrocities, he was overcome with emotion.

“YIPPEEEEEEEE!”

Franklin was ecstatic because both the scalps story and the Prince’s letter were pungently powerful propaganda — perpetrated by the most popular polymath of Pennsylvania, Franklin himself.

Yes, Ben Franklin was a provocative propagandist and proficient provocateur, having been a nice newspaper publisher among his many professions. To create the Indian scalping story, Franklin forged not only the story but the entire newspaper, deepening the deception by adding some genuine news articles and even some genuine advertisements. To create the Prince’s letter, Franklin simply wrote it.

Meanwhile, the American inventor of the lightning rod was also electrifying Paris high society. Proper Parisian ladies honored him by including in their towering wigs a fashionable lightning rod. (It was also prudent, given how tall their wigs were.) Sympathetic European officers, eager to join Washington’s army, asked Franklin for letters of recommendation — men such as the Marquis de Lafayette and Baron von Steuben. On the other hand, so many of them pestered Franklin for letters that, ultimately, Franklin created a form letter:

“The bearer of this, who is going to America, presses me to give him a letter of recommendation, though I know nothing of him, not even his name. I must refer you to himself for his character and merits, with which he is certainly better acquainted than I can possibly be.”

.

Ben Franklin became the toast of Paris.

And in Paris, that’s plenty of toasts.

Paris was fun. But unless Franklin maneuvered France into a more formal alliance with America, and thus the direct assistance of French soldiers and warships, the American Revolution might end up only a footnote in a philosophy book at the Sorbonne. So Franklin suggested to a British diplomat stationed in Paris that, well, a reconciliation between England and America might not be such a bad idea. How about it? You hurt us a little. We hurt you a little. But we made our point and, hey, it’s all in the family. And besides, we Americans like talking with pompous British accents.

Not that Franklin believed any of this. (Well, maybe the part about accents.) But the many French spies in Paris spying upon Franklin did believe it, or at least they assumed that he believed it. Before long, the King of France and his ministers uttered a collective comment upon this fast-developing situation.

“Oh merde!”

That quaint French word refers to manure.

Soon thereafter, America got its formal alliance with France.

General Washington wrote, “The necessity of procuring good intelligence is apparent and need not be further urged. All that remains for me to add is that you keep the whole matter as secret as possible. For upon secrecy, success depends.”

Ben Franklin might beg to differ.

Respectfully (because all my readers deserve respect),

Reginald Dipwipple

Secret Agent Extraordinaire

.

Franklin in disguise: “Yes, of course, I’m a Good Old Boy from the American frontier. Can’t you tell from my hat?”